The last king in South America boasts a lineage dating back centuries. Yet Julio I’s crown and leopard-trimmed robe are rarely seen in the humble grocery shop he runs with his wife, Queen Angélica, in a small jungle village in rural Bolivia.

The 10th anniversary of the reign of Julio Piñedo, 75, falls this December, but, he says, “there’s nothing special planned” for the occasion. His symbolic dominion extends to a few dozen rural communities and the city dwellers that make up the 25,000-strong Afro-Bolivian community. But now, partly thanks to Piñedo’s offices, this long-neglected group is stepping out of the shadows.

“Without doubt the king’s role is important,” says Zenaida Pérez, 25, coordinator of the Afro-Bolivian Language and Culture Institute, part of umbrella organisation Conafro. “He represents much of what our Mother Africa has left us.”

From the 16th century, Europeans shipped west African slaves in their thousands to colonial Bolivia. Many perished in the deadly conditions of the infamous Cerro Rico silver mine, the churning motor of Spain’s imperial economy. “Of those they brought to work in Potosí, half of them died,” Piñedo reflects.

As the silver boom slumped, wealthy landowners brought the survivors and fresh captives to the humid Yungas region to work the land. It was here, local legend tells, that Piñedo’s ancestor, Prince Uchicho, was recognised. “He was bathing in a river,” says Angélica, “And [his companions] discovered his tattoos showing that he was king.”

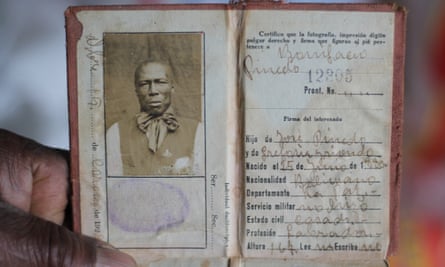

From then on, the king protected the community from the worst of their landlords’ depredations. Piñedo’s grandfather, Bonifacio I, is remembered as a particularly stalwart champion. Yet when he died in 1954, Bolivia was undergoing a revolution, and inherited status was out of fashion. The royal line skipped Piñedo’s mother and was revived more than 40 years later by local elders in an effort to boost Afro-Bolivian culture and traditions.

“It was a moment of pride for us Afros,” says Piñedo, recalling his coronation as a rainstorm drums on his zinc roof in Mururata. The greater national visibility that followed has helped combat discrimination, he explains. “Before we were called negritos or negros – but now things have changed, and they’ve started to call us Afros.”

The king, along with most of his rural subjects, still cultivates coca, sugarcane, bananas and coffee to survive, but more young Afro-Bolivians are going to university, and there are plans to encourage tourism in the area.

“We have Afro-Aymara couples … now, we get on – we share friends, families and pastimes,” says Jhony Zavala, 42, a community leader in the nearby village of Tocaña. One is traditional saya music – itself a political tool, explains Pérez. “We’re a small people in Bolivia, but the drums replicate our voices. They say they’re the voice of our ancestors, too.”

Bolivia’s 2008 constitution explicitly recognises Afro-descendants, while recent years have seen the first Afro-Bolivian legislators and civil servants. Remaining battles include writing Afro-Bolivians back into the history books. “Mental slavery, which has stopped our people from demanding their rights, is the hardest thing to break,” adds Pérez. Piñedo would like to see a few more Afro-Bolivian faces selected for the national football team.

In 2016, Julio, Angela and their grandson and crown prince, Rolando, visited Senegal, the Congo and Uganda with two journalists to track down their relatives. The experience was bittersweet. They marveled at the absence of white faces, but struggled to make themselves understood.

A guide took them to the supposed royal seat of their ancestors. “We must have travelled for six hours. We got to a very pretty palace, but it was abandoned,” says Piñedo, sadly. The caretaker said that the occupants had long since gone, perhaps to another country.

Rolando, 23, is studying management and hopes to work in Madrid once he graduates. “I’d like to work there for a bit, and afterwards return … I want to keep alive the traditions.”

Yet the house of Piñedo is not entirely secure. There are political rivals, and those who see the monarchy as a relic. “That’s why I want to continue my studies and become the best person I can be,” says Rolando. “If it continues, it would be a joy to keep it going,” he shrugs, with a smile.

“It’s complicated,” admits King Julio I, preparing to go to tend his coca plants. “We’re calling for the young people to maintain the customs of our grandfathers …there’s always going to be change, but we want to keep what’s right.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion