The workday was just beginning in Turkey when Mehmet Ali Yalçındağ reached the nation’s president by phone. Yalçındağ was calling from Trump Tower in Midtown Manhattan, where it was past midnight — the end of a long Election Night in November 2016. Yalçındağ had come to the hulking black skyscraper with the oversize gold letters above the entrance to show support for his business partner Donald J. Trump — on a night few but the true believers expected the brash real estate tycoon to emerge as the next president of the United States.

Despite a majority of the electorate viewing him unfavorably, the stars aligned for Trump: Mainstream Republicans, Democrats, and the media stumbled on how to handle an unconventional candidate. Trump faced a flawed and unpopular opponent in Hillary Clinton, who misread the electorate and ran a poor campaign. FBI director James Comey broke with precedent and inserted himself into the election, parceling out negative judgments and suggestive details on what turned out to be a fruitless Clinton email investigation. And Russian president Vladimir Putin launched a massive cyber-attack on the United States in an attempt to influence the outcome.

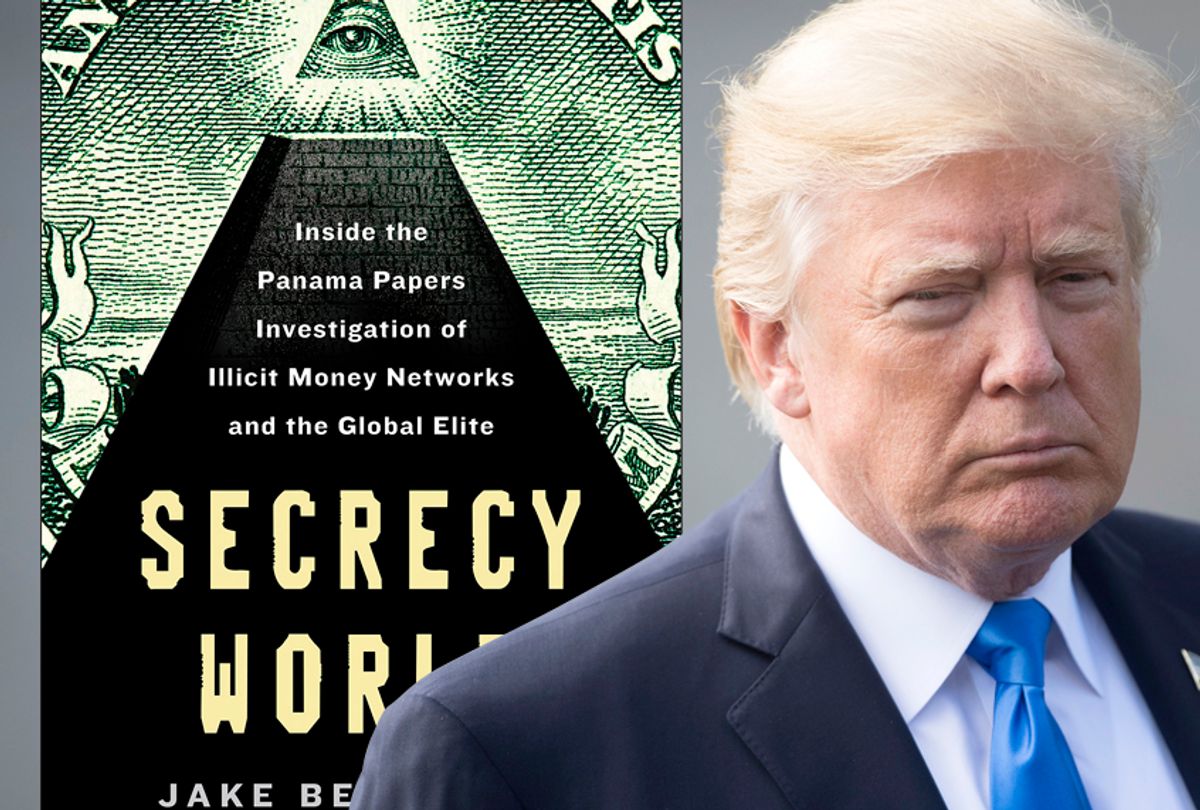

The Kremlin-backed attack included hacking the email server of the Democratic National Committee, flooding social media with fake news, and attempts to compromise individual state election databases. According to a declassified intelligence assessment, Putin targeted Democrats and the U.S. electoral system in part because he was furious over the Russian revelations contained in the Panama Papers. The details about the illicit cash flows swirling around the Russian leader had filled newspapers and news broadcasts worldwide. Putin blamed the damaging data leak on the Obama administration.

However, Putin’s tilt toward Trump appeared to have been motivated by something deeper than a desire for revenge against Hillary Clinton and the Obama administration. Putin and Trump shared a similar zero-sum worldview and a penchant for operating in the shadows. Each man viewed the idea of a free press with contempt. They both believed that financial interests should be passed down to their children to create family dynasties. For years, Russian money helped keep Trump’s business empire afloat. He and his campaign staffers maintained multiple business connections with Russian oligarchs closely allied to Putin.

Trump and Putin were also both conversant with the secrecy world, practiced hands at using anonymous companies to wall off their activities and keep their business affairs secret. During the campaign, Trump reported that he had 378 individual Delaware companies, but the full extent of his business dealings remained hidden. Trump was the first presidential candidate in forty years not to release his tax returns.

Though Donald Trump did not personally interact with Mossack Fonseca (Mossfon) — the Panamanian law firm implicated in the Panama Papers leak — the Trump Organization engaged in real estate transactions with Panama-based Mossfon companies as early as 1994. Real estate developers, buyers, and sellers have long operated in the secrecy world. Trump and his associates were no different. The Panama Papers reveal at least nine of his foreign business partners had connections to Mossfon. Several of Trump’s business partners who used the secrecy world allegedly mixed legitimate businesses with illegal activities such as prostitution, bribery, and tax evasion. When asked about such allegations, Trump claimed ignorance.

Alexander Shnaider and Eduard Shyfrin, who developed the Trump hotel in Toronto through a Guernsey company, conducted much of their business offshore and are shareholders of at least five companies in the Mossfon files. One company, Midland Resources Holding Limited, sold at least half of its shares in a steel plant to a collection of offshore companies acting as fronts for the Russian state-controlled bank Vnesheconombank, or VEB. The deal occurred as the developers battled cost overruns and delays on the condo-hotel development, which, like so many other Trump projects, ended in lawsuits and recriminations.

In his campaign and administration, Trump surrounded himself with people who were connected to the Panama Papers data. Trump’s son-in-law, Jared Kushner, received financing from the Steinmetz family, who used multiple Mossfon companies and HSBC bank accounts. Kushner also did a $295 million real estate deal with Lev Leviev, an Israeli oligarch known as the “Diamond King,” who had at least three Mossfon companies and a trust. Leviev was a business partner of Russian-owned Prevezon Holdings, which was implicated in the Magnitsky case, an alleged $230 million theft by Russian mobsters. Prevezon’s assets were frozen by U.S. prosecutors while they investigated money laundering in the case. After the firing of U.S. Attorney Preet Bharara, the Trump Department of Justice abruptly settled with Prevezon for $5.9 million.

Trump’s campaign chairman, Paul Manafort, had business relationships with two Russian oligarchs — gas billionaire Dmitry Firtash and metals magnate Oleg Deripaska, a confidant of Vladimir Putin — both of whom had offshore companies with the Panamanians. Sebastian Gorka, former deputy assistant to the president, appears to have written to the law firm in 1992 about a company he was researching for his employer. Mossfon provided Gorka with information on the company and then invoiced him $125. Gorka refused to pay, insisting that the inquiry had been “on a casual basis,” and no fee had been discussed. Mossfon did not pursue payment.

At Trump Tower on Election Night, Yalçındağ handed his cell phone to the new president-elect. Turkey’s president, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, thus became the first world leader to congratulate a still-stunned Donald Trump on his victory. Trump had spent the final hours of the evening glued to the television, in near silence. According to an account of the conversation between Trump and Erdoğan, procured by the Turkish journalist Amberin Zaman, the president-elect referred to Yalçındağ as his “close friend” and told Erdoğan that Yalçındağ was “your great admirer.”

Trump’s support was a fortuitous stroke for Yalçındağ, who was desperate to be in the Turkish president’s good graces. Erdoğan had attacked his family’s company, Doğan Holding, a sprawling financial empire with significant Turkish media and oil interests, several of which had Mossfon connections. Erdoğan’s government had pursued Doğan over allegations of massive tax evasion and critical media coverage, levying billions of dollars in fines against the conglomerate.

Trump had long made a practice of consorting with dodgy characters for financial gain. News organizations reported that in New Jersey and New York he regularly conducted business with people connected to the Mafia. He had leased the site for his first casino from two men with Mob ties. Building unions known to be controlled by the Mob continued to service Trump’s worksites, even when they went on strike elsewhere. Suffering no ill consequences for his sketchy associations, Trump doubled down when he was later forced to transform his business.

By the mid-1990s, Trump’s bankruptcies and penchant for civil lawsuits dried up funding from most U.S. banks. He moved away from developing properties himself, focusing instead on selling his brand and seeking revenue abroad. He now licensed “signature” developments that bore his name and were built to his precise specifications. In the case of hotels, the Trump Organization would often manage the property for a percentage of the revenue. Outside the United States, he became even less picky about the origins of the money that came his way.

Following the 2016 election, Trump’s foreign business entanglements escalated to national security and constitutional concerns. While his business partners hoped to profit in new ways from their relationship with the president of the United States, it became increasingly difficult to determine whether the Trump administration’s actions were in the public interest or in pursuit of personal gain. At the same time, the White House, allied with a Republican Congress, pushed a new policy approach toward the secrecy world that better reflected their shared laissez-faire ideology.

During its eight years in office, the Obama administration had attempted to nudge government policy in the direction of increased transparency and oversight of the offshore system. In addition to signing the Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act in 2010, the administration tried to tamp down on states like Delaware, Nevada, and Wyoming that offered themselves as safe harbors for foreigners bent on tax evasion and criminal activity.

Faced with intense opposition from lawyers, bankers, and state officials, the Obama administration opted for baby steps to combat the problem. It passed a pilot project that forced real estate agents in Miami and New York to report the actual beneficial owners of property purchased with cash by an anonymous company, although the rule required only the names of those who owned 25 percent or more of the equity interest. In 2017, Treasury expanded the program. The Internal Revenue Service also issued a rule that foreign-owned limited liability companies based in the United States needed to obtain an Employee Identification Number (the corporate equivalent of a Social Security number, necessary for tax collection), to keep books and records available for inspection, and to designate a Responsible Person, who had control over the company.

Most important, the Obama administration had increased taxes on wealthy Americans. Trump and the Republican Party saw taxes, particularly on the wealthy, as theft by government edict to be eliminated whenever possible. Under Obama, efforts to increase funding for the resource-starved Internal Revenue Service, the frontline troops in the fight to stop Americans from evading taxes through the secrecy world, died in the face of Republican resistance. During the campaign, Trump praised himself for doing everything he could to escape paying taxes. When Clinton accused him of avoiding federal income tax for years, Trump responded, “That makes me smart.”

Within weeks of Trump’s inauguration, the new president and the Republican Congress signaled an end to Obama’s approach to the secrecy world. In one of its first significant votes, Congress repealed an anticorruption measure that had forced oil, gas, and mining companies to file an annual report to the Securities and Exchange Commission detailing their payments to foreign governments where they did business. The intent of the original legislation had been to reduce bribery, and its abolition was a gift to the extractive industries that had helped fund the Republican Party’s political campaigns through millions of dollars in contributions. The repeal could also benefit several of Trump’s foreign business partners, who were heavily invested in the oil and mining industries.

Trump was already on record against efforts to tamp down on foreign corruption. In a phone-in appearance on CNBC in 2012, he called the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act, which forces U.S. companies to investigate the people with whom they do business to ensure that they are not cooperating with illegal activities, “a horrible law,” which should be changed. “Every other country goes into these places and they do what they have to do,” Trump said.

If American companies avoided bribery, “you’ll do business nowhere,” said Trump.

Shares