Hong Kong’s role in the yuan’s ongoing journey to achieve global prominence

As a finance professional working in Hong Kong for the past two decades, John Tan Ming-kiu never dreamed he would end up dealing with Beijing regulators, nurture a Taiwanese banking franchise, or see the dim sum bond market kick off.

But the changes heralded by Hong Kong’s handover to Chinese rule in 1997 saw his working life take many unexpected turns.

Tan, currently managing director of Greater China and north Asia head of financial markets at Standard Chartered Bank, started out trading US and Hong Kong dollars in the currency and derivatives markets, which were considered among the city’s main financial businesses prior to the handover.

But things started to change when China began allowing foreign banks to incorporate on the mainland and they actively recruited Hong Kong talent to develop its fledging capital markets. The yuan was embarking on an upward trajectory that would last for the next eight years.

“If you were in finance in Asia, this would be the golden 10 years to be in the industry and to be involved with the rise of China,” Tan said.

But it was not until the 2008 global financial crisis that the evolution of the yuan really took off, triggering China’s ambitions to foster a currency that trades relatively freely – though it has been a case of one step forward, two steps back on achieving a truly convertible yuan.

If you were in finance in Asia, this would be the golden 10 years to be in the industry and to be involved with the rise of China

“I remember bringing my team to Beijing to meet with the People’s Bank of China and the China Banking Regulatory Commission to discuss the issues occurring abroad,” Tan said. “That was the start of the communication channels, and from then on they kept asking about a roadmap for the yuan to internationalise.”

Tan, an amiable 53-year-old, turns nostalgic as he describes his appointment as CEO of Standard Chartered Bank Taiwan in 2014. His sense of accomplishment from that career move partly derives from achieving the unfulfilled dreams of his late father, who was never granted visa-entry to Taiwan after facing the many hardships that came with fighting in the Sino-Japanese war.

To Tan, the fact that less than 2 per cent of the total yuan pool is being used overseas – compared to 30 per cent for US dollars used outside of the States – means there is still huge growth potential in the yuan’s journey to becoming a global currency. And foreigners’ confidence and trust in Hong Kong’s legal and regulatory framework provides room for the city’s financial markets to play an important role.

“The Hong Kong dollar only serves a small city but we need to look at the big picture,” Tan said. “So it’s really up to the younger generation now to grasp the opportunity to participate in these historical times.”

Melody He Xian, 28, in charge of ETF and index solutions and head of structured solutions at CSOP Asset Management, who came to Hong Kong in 2011, agrees.

She believes working at a Chinese financial institution in the city has allowed her to get ahead in a rapidly changing industry, enabling a deeper understanding of official policies and developments in China. CSOP was among the first batch of institutions allowed to sell Renminbi Qualified Foreign Institutional Investor (RQFII)-related products in 2012 and currently has a RQFII quota of over 46 billion yuan (US$6.8 billion), the biggest for any institution.

“You need to run faster than anybody else to keep from being expelled in this industry. Competition will increase,” He said.

Since McDonald’s became the first multinational corporate to raise funds through the sale of dim sum bonds in 2010, the variety of yuan-products available in Hong Kong has expanded into yuan hedging instruments such as yuan futures, yuan options and listed currency indices, as internationalisation of the yuan progresses.

The new Bond Connect scheme, which comes two years after the launch of Stock Connect, is the fourth programme that allows foreigners to invest in onshore bonds, after the QFII, RQFII and the China interbank bond market (CIBM) direct schemes.

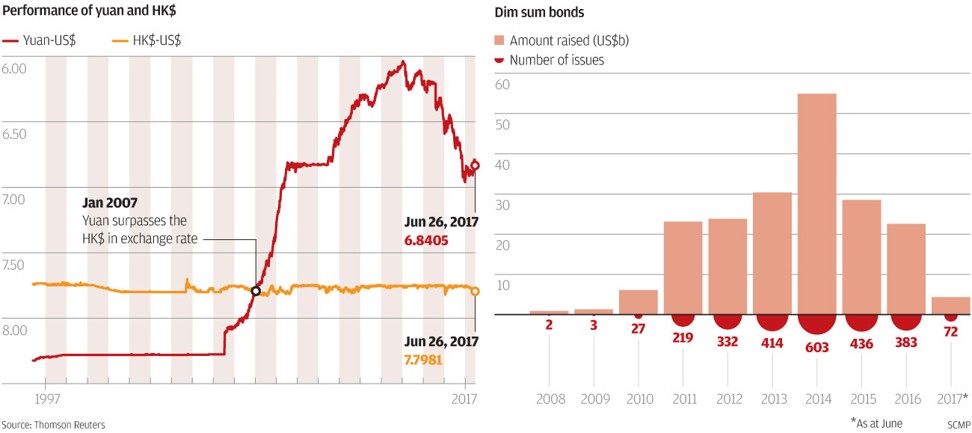

But China’s financial reforms have succumbed to strong headwinds in recent years, with the currency reversing into a slide because of slowing economic growth. Annual issuance in the dim sum bond market peaked at the equivalent in yuan of US$54.9 billion in 2014 before slowing to US$28.5 billion in 2015 and US$22.6 billion in 2016, according to Thomson Reuters data.

Foreign observers have often accused China of making mistakes, such as intervening in the stock market crash of 2015. The implementation of capital controls may have helped to artificially halt the depreciation of the yuan for now, but it has also caused a loss of confidence among foreign companies who are worried about repatriating their money.

Tan refers to this “trial and error” approach in government reform policies with a famous Chinese proverb that means “crossing a river by feeling the stones,” or treading cautiously in times of uncertainty.