The Strange Case of a Port and Its City

Currently, Bayport uses 3,330 feet of dock space, which is to say half of its potential capacity. But more ships are coming. Larger ones, too. Davis thinks that within the next decade, the PHA will be handling in the neighborhood of 125 million tons of cargo annually at Bayport and Barbours Cut, its other main facility. That’s nearly three times as much as it saw last year. Yet he insists that his team is prepared to manage the spike in business, even if Davis can’t quite predict how they’ll pull it off: “We’ve never reached a point with the container terminals where we’ve folded our arms and said, ‘Well, we’re done, all done!’ We’re always expanding.”

A seagull flaps its wings in front of Davis’s windshield. Somewhere out of sight, a foghorn wails.

Image: John Dunaway

“The backbone of an industrial giant”—that’s how a local magazine story described the Ship Channel in 1957. It’s certainly a powerhouse, one that’s only grown stronger with time. A recent study commissioned by the PHA determined that Houston’s port was responsible for 56,113 jobs in 2014 and generated $264.9 billion in statewide economic activity, accounting for a full 16 percent of Texas’s gross domestic product. It boasts the country’s largest petrochemical complex, ranking first nationally in total waterborne tonnage and second in value of goods transported. And port activity is poised to accelerate with the long-awaited expansion of the Panama Canal, opening this summer (more on that later).

From this vantage point, the port’s future looks rosy, bright and, at the moment, strikingly different from the city beyond the Ship Channel bridge. Or as Patrick Jankowski of the Greater Houston Partnership puts it, “just because oil prices have fallen, that doesn’t mean ships are going to stop calling.” As the city itself suffers through an economic slowdown that has left whole office buildings vacant, land near the port’s container terminals “is becoming pretty doggone scarce,” according to industrial real estate broker Kelley Parker. And even as tens of thousands of Houstonians have lost their jobs, Steve Nerheim, director of the Coast Guard’s Vessel Traffic Service, gazes out at the water and wonders, what recession?

“It’s like this other world,” says Traci Koenig, a former director of economic development at the Economic Alliance Houston Port Region. “Unless you’ve been down there, it’s very insular, the ultimate good ol’ boys club.”

Two different worlds. Despite their proximity, that’s what the Ship Channel and the city of Houston sometimes seem like. Both are big, powerful, complex and misunderstood, and each is unthinkable without the other. Nonetheless, they inhabit separate realities, each a mystery to the other.

Image: Tanyia Johnson

J.J. Plunkett is always thinking about traffic. Tall, tanned and broad-shouldered, he is the chief operating officer of the Houston Pilots, an association of 96 master mariners whose job it is to guide ships—1,600 gross tons or larger—into and out of the Port of Houston. “Most of them are Type-A personalities, hard-charging kind of guys,” Plunkett says of the Pilots, who go through a comprehensive three-year training program. “They are proud of their tradition of taking 10 pounds of potatoes and stuffing them into a five-pound sack.”

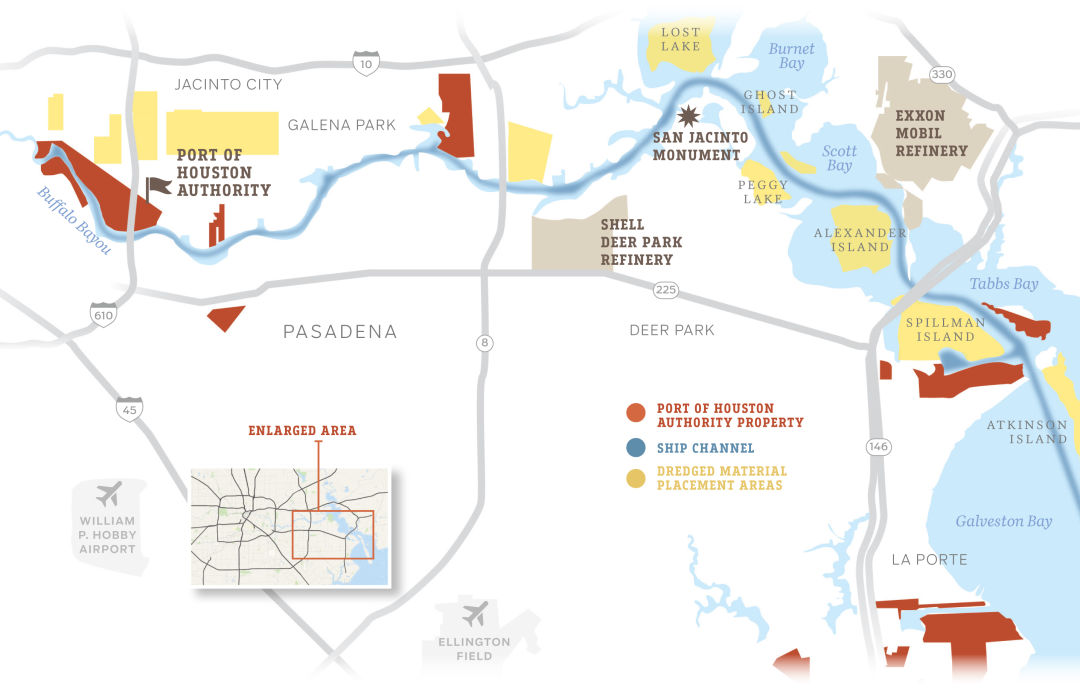

The Pilots have been doing just that for nearly a century. Originating a mere six miles from Houston City Hall, the 52-mile-long channel—530 feet at its widest point, 300 feet at its narrowest, never deeper than 45 feet—snakes through the city’s east side before jutting south into Galveston Bay and eventu- ally flowing into the Gulf of Mexico. Last year, 8,000 ships and 200,000 barges motored up and down it, servicing Houston-area firms clustered along the slim, murky waterway. The PHA has jurisdiction over roughly 15 percent of the docks, its longshoremen handling the vast majority of Houston’s container trade. The rest of them are privately owned by 150 different companies, most of which export and import raw materials to and from all corners of the world: petroleum, steel, petrochemicals, plastics.

Tanks and refineries pepper the terrain immediately south of the channel, off Hwy 225, a spaghetti bowl of pipes and valves and the occasional flame-spewing flare. Within this Mad Max landscape sits the Pilots’ dispatch center, inside a dull brown building with a ceremonial bronze anchor out front. Inside, Plunkett walks down a yellow hallway and into a dim room where two pilots in jeans and polo shirts are seated at L-shaped desks. Flat-screen monitors are mounted on the wall in front of them, the middle one showing a live video feed from the U.S. Coast Guard’s Vessel Traffic Service. On the right is an electronic map of Galveston Bay covered in colorful dots. “The ships have a transponder on them, like an airplane does,” Plunkett says. He points to the display. “Here we can see where they are in the system.”

Ship owners need give only four hours advance notice when requesting pilot service, and the calls come in constantly, 24 hours a day. At any given time, there are 90 to 95 barges and ships scurrying through the congested slip, and there would almost certainly be collisions if not for the Pilots. “It’s not like going into San Francisco, where there is lots and lots of water with big, wide lanes,” Plunkett says. “For us, when two ships pass in the Houston Ship Channel, they could be 60 feet apart—each doing, say, 12 knots. It goes by really fast.”

It’s an important job, and yet, Plunkett often leaves people confused at cocktail parties. When he tells them where he works, they ask what airline he flies. When he corrects them, “they’ll say, ‘There’s a port in Houston?’ And I have to tell them, ‘Yes—yes, there is!’”

Oh, and those get-togethers he attends? They’re in Sugar Land.

To some extent, Houston’s ignorance of its port can be traced to geography. The Ship Channel flows east and out—away from the Loop, away from the well-to-do suburbs, away from the everyday action. “If you’ve been to a port like San Diego or New York, it’s inescapable, it’s part of the cityscape. The town is built around it,” says the Coast Guard’s Nerheim.“I think the Port of Houston is a theoretical construct to most Houstonians. They know it’s here, [and] they couldn’t find it.”

You can’t really blame them. Houston’s port looks and feels different from nearly every other in North America. For one thing, it’s landlocked, with no beaches the public might frequent, no boardwalks on which they might stroll. It’s also dominated by the energy industry, with petroleum products making up almost 40 percent of the port’s total foreign trade. (Plunkett estimates that half his Pilots’ trips involve steering tankers into and out of the port.)

The oil companies don’t seem to mind the Ship Channel’s unwelcoming vibe. On the contrary, they revel in it. A favorite term among industry types—inside the fence—refers both to how petrochemical companies see themselves and how they prefer to conduct their affairs. To an extent, that stance is understandable, given the hazards posed by the materials they produce, not to mention the need to safeguard proprietary information in a competitive marketplace. But is the port’s fence too high?

“Okay, what are you going to need? A drop of blood? First-born son? What do I need to bring today?” says Koenig, recalling how she and her colleagues used to joke about the companies’ cumbersome restrictions. Absent a TSA badge, or the services of a clever attorney, there’s no getting in. Even a visit to the PHA’s headquarters, underneath the Ship Channel bridge, can trigger a complete car inspection.

Image: John Dunaway

Steps from the Turning Basin, on a wall at the Greater Houston Port Bureau, hangs a six-by-eight-foot aerial map of the Ship Channel depicting the names and locations of companies the trade group represents, 210 in all. The Port Bureau president grabs an orange sticky note from a coworker’s desk and slaps it onto the map’s top left corner.

“So there’s downtown. I’ve just covered it up,” says Captain Bill Diehl, a compass pin on the lapel of his sharp gray suit, a waterproof athletic watch on his wrist. He pauses a beat, then puts the same sticky atop ExxonMobil’s refinery in Baytown. The orange square is dwarfed by the complex. “I’d say that’s about three times as big [as downtown]?” Diehl estimates, marveling at the scale. “As you’re coming down 225, all you’re seeing is industry. You don’t know how deep it is. But it’s deep.”

That depth has only grown since 2009, when Diehl arrived at the Bureau, where he and his colleagues track local ship movements and broader industry trends. “Our job is to be curious,” as he puts it. The Bureau also exists to facilitate communications among its members, and to remain impartial when disputes arise. (“The Switzerland of the Port,” they call themselves.) As such, there are few people as keenly aware of the Ship Channel’s present realities as Diehl, and few better equipped to forecast its future.

Before his present job, Diehl spent 27 years as an architect in the Coast Guard, where he established that agency’s first salvage engineering team even as he bounced around the continent soaking up technical expertise. One of his last assignments was in Panama; from 2004 to 2006, he served as a liaison between the American government and the Panama Canal Authority, advising the Central American nation as it laid the initial groundwork for a widening of the historic, 50-mile canal, one which could ultimately double the amount of goods that pass through. At the time, a Coast Guard admiral told Diehl that Panama was a “dead-end job.” It’s proving to hold greater possibilities than either man expected.

These days, Diehl can clearly see how Houston—with its dense concentration of refineries and petrochemical plants, 1,775 miles to the north—could leverage the Panamanian passage he helped devise. Shale plays and fracking throughout the state have unlocked an abundance of natural gas, a cheap feedstock that’s driving investments in the chemical industry, some $50 billion in the region alone. Polymers, resins and other refined products—the primary components in most consumer goods—are suddenly affordable to produce, in bulk, at home. And potential buyers are everywhere. “We’re going to want to export those to emerging markets, from Houston into the Panama Canal, to China and Vietnam and Australia and Indonesia,” says Jankowski of the Greater Houston Partnership. “It’s a conduit, like adding additional lanes on the freeway.”

For its part, the PHA predicts a 5 percent annual uptick in container trade over the next half-decade, and that’s before you factor in the Panama Canal expansion. One recent study concluded that by 2020, as much as 10 percent of the container traffic between East Asia and the U.S. could shift from the West Coast to ports in the Gulf of Mexico and Eastern Seaboard, all thanks to the canal. The study also predicted that a “battleground region” will emerge along the length of the Mississippi River, one in which ports in the south and east compete for the business of cities like Chicago and St. Louis, both of which are mainly served by trains and trucks dispatched from California.

For much of the Midwest, Houston—by way of the Isthmus of Panama—could soon present a cheaper and more reliable option. “Los Angeles–Long Beach and Houston have basically emerged as the two super-ports of North America,” says J. David Rogers, professor of geological engineering at the Missouri University of Science and Technology. “They are very forward-thinking and behaving strategically.”

Of course, all of these projections are just that—educated guesses. Still to be announced (at press time) is the Panamanian tariff structure, which will determine how attractive the wider route is to shipping companies. And there’s ongoing uncertainty about the Port of Houston too. Its silty bottom and penchant for unpredictable weather mean that the channel must be constantly dredged, something that, if mishandled, could disrupt or deter future traffic. “We dug a 45-foot ship channel on a 12-foot bayou and called it the Port of Houston,” Diehl says. “And it wants to return to 12-foot bayou.”

And then there’s that other question, perhaps the hardest of all to answer: How will the port’s growth change its relationship to the struggling city on the other side of the bridge?

In his office, the captain reclines in his leather chair. A coffee table book, Houston Ship Channel, Open to the World, is perched, appropriately, on his coffee table. He remembers one day, back in Panama, when the Canal Authority asked him to write a 20-page report. He turned in a draft that he deemed thorough and clear, “some of my best work.” A Panamanian called the research “unacceptable,” too short-sighted. “We make decisions that will last 100 years into the future,” they told their American liaison. For a moment, Diehl just stared. “I was like, ‘well, nobody can predict that!’”

Texas Chicken; two ships meet on the Ship Channel.

Image: John Dunaway

Shelley spends lots of time out there now, as executive director of Air Alliance Houston, an environmental nonprofit. It’s a gig he came to obliquely. In 2008, a class project at the University of Texas, where he went to law school, led him to a “toxic tour” of neighborhoods abutting the port. Then as now, most are working-class and predominantly black and Hispanic. “It was a portion of the city I had never seen, communities I had nothing in common with, no interaction with,” he remembers. “I was completely ignorant of the burdens of some of these communities. ... I felt almost ashamed.” On the spot, he decided he’d do something to help, switching his concentration to environmental law and the intricacies of the Clean Air Act.

Air Alliance Houston’s six-person staff conducts research and lobbies lawmakers around air-quality issues from their EaDo office. In his spare time, Shelley leads toxic driving tours of his own, just like the one that hooked him nearly a decade ago. It’s his favorite part of the job.

“I don’t know why this road is public. Most places, they would have closed a road like this a long time ago.” He layers plastic sunglasses over his prescription frames and angles his gray Prius down Tidal Road in Deer Park. A phalanx of plants hug both sides of the two-lane street—Shell, Intercontinental Terminals, Dow. Pipes and foreboding smokestacks crisscross overhead; an unidentifiable stench wafts through the driver-side window, and possibly into the patchwork of bungalows a few blocks south, across the Pasadena Freeway.

Shelley is chatty and driven, full of technical knowledge. With experience, he’s grown more brazen about going places he shouldn’t (“you’ll eventually get stopped by somebody, and you play dumb”), but he’s especially fond of Tidal Road. “You can drive right into the middle of everything,” he says. “It gives you a good sense of what it’s like to be around here.”

Shelley’s tours usually leave him with a headache. For a while he thought it mere coincidence, or maybe a psychosomatic response, but the headaches kept recurring. That’s not especially surprising: Health risks incurred by Houstonians living in the port’s footprint are well documented. In 2007, the University of Texas School of Public Health published a landmark, 18-month study confirming that children who resided within two miles of the Ship Channel had a 56 percent higher risk of contracting acute lymphocytic leukemia than children living more than 10 miles away. Last year, the Texas Department of State Health Services found higher than expected levels of other cancers in east Harris County: childhood lymphoma and melanoma, cervical and brain cancer. Air Alliance Houston and its allies have conducted their own studies, too. While not scientific, a 2013 survey of residents revealed that rates of asthma and other respiratory diseases were more than two times higher near the port than they were elsewhere in the state.

It’s an especially painful corrective to present received wisdom. The port and the city it bisects are not separate at all, however much each would like to think otherwise. And their mutual ignorance of this connection leads to all sorts of consequences—some good, some bad, some deadly.

From Tidal Road, Shelley curls down a gravel path leading to a clearing with a “nice little view.” A green container ship wades in the blue water ahead. He parks and gets out of the car, running his hands through his wavy hair. “You can tell I enjoy being out here and seeing this stuff,” he says, pacing about. Shelley’s dad, ironically, worked in finance for oil companies; father and son love to talk shop. “I find it interesting. Every time I come out here, I find some- thing new, see something different going on.” But he’s conflicted, too. Proud of Houston and its role in the world economy, he also understands better than most the unintended costs of that industrial growth: “It mostly makes me sad, right? There are people who have to live around this stuff.”

Last year, the EPA issued a new rule requiring refineries to install monitors that measure benzene, a cancer-causing chemical, along those fences that line their properties. It was an issue for which activists like Shelley had pushed forcefully, but such victories are few and fleeting. There are too many moving pieces, too many deep-pocketed stakeholders. “We work on the margins. We accept defeat,” he says with a smirk. “But we also have job security. There’s plenty of work to be done.”

A Houston Pilot steers a Chinese ship.

Image: John Dunaway

The wood-paneled schooner leaves its dock at the terminus of the channel, trolling casually past Brady’s Landing and under the 610 bridge before reversing course. Giant freighters power by on the starboard side.

Debris washes up along the banks. There’s a scrap metal plant, with gnarled wires and rods piled dozens of feet high, and factories stacked on top of each other, nestled right up to the shoreline. It is an ugly yet powerful seascape, even scenic in its own unique way. If the 90-minute trip—an ocean cruise through the city’s very unnatural trade infrastructure—induces an odd sensation, it also offers perhaps the best evidence of a new dynamic at work between Houston and its port, or at least the desire for one.

Often booked up a few weeks in advance, the PHA- operated Sam Houston Boat Tour is popular with old timers, young families, school groups. The Texas history embedded here is surely part of the draw—the San Jacinto Monument, the site of Santa Anna’s capture (now under a fishing advisory due to pollution), the South Side Docks that shipped cotton 100 years ago. But mostly the visitors come for the port itself, to catch a glimpse of the downtown skyline on clear mornings, to come to terms with a mysterious seaway both near and distant. Guiding the passengers in more ways than one is Doug Mims, the schooner’s captain, whose self-stated goal is that they see “all the people who are affected by the commerce moving through here.”

It’s a mission of understanding not unlike Leslie Bowlin’s. She too wants to improve the relationship between Houstonians and the 52 twisty miles of the Ship Channel. Bowlin is the peppy director of the Houston Maritime Museum, which up till now has been buried in a clapboard building behind the Texas Medical Center. This fall, however, the institution will break ground on a 38,000-square-foot waterfront site next door to the Sam Houston launch point. The architectural firm Gensler designed the property and local construction company Tellepsen will build it out, both at discounted rates. The new structure will feature interactive exhibition halls, an expanded research library and a children’s boat pond, along with additional education and event spaces. “At the end of the day, we’re all related to this maritime world, whether we know it or not,” Bowlin says.

Back on the water, Genaro Ambriz, Mims’s co-captain, guides the schooner past the hulking Onego Pioneer, a yellow cargo vessel from Cyprus. The tour boat rocks in its wake. Before he got this job, the port was as mysterious to Ambriz as it is to seemingly every other Houstonian. Which is interesting, because Ambriz grew up just a few miles miles away from the port, in Magnolia Park.

“It’s funny,” he says. “As close as I lived to it, I never came on the boat just to ride as a kid.” Ambriz adjusts his depth finder—42 feet—and fiddles with the control deck, staring out at calm waters. “It’s a free boat ride! I don’t know why they never brought us over.”