A Soyuz rocket soared into orbit after firing off a launch pad in the Amazon jungle Friday, deploying two satellites nearly 15,000 miles above Earth to expand Europe’s Galileo system helping locate automobiles, airliners, and millions of other users around the world.

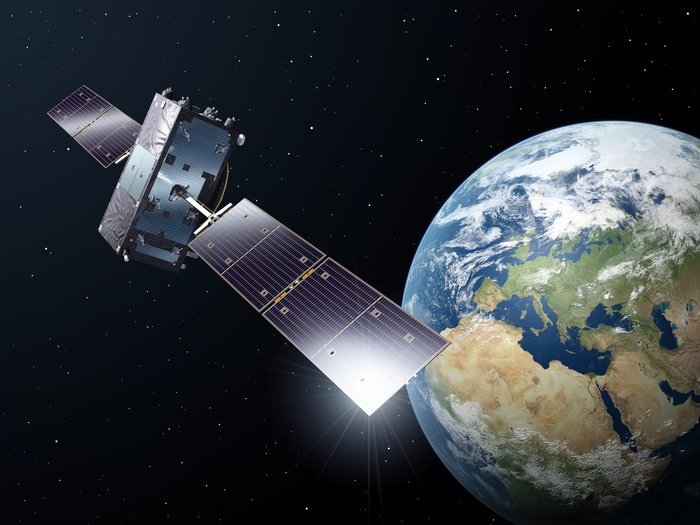

Fastened side-by-side inside the Soyuz rocket’s nose fairing, the satellites are set to become the seventh and eighth members of the Galileo navigation system, a civilian-run analog to the U.S. military’s Global Positioning System.

The Soyuz booster spun up its five main engines as the final few seconds of Friday’s countdown ticked toward liftoff at 2146:18 GMT (5:46:18 p.m. EDT), lighting up Europe’s spaceport in French Guiana as petal-like clamps opened at the launch pad and the rocket bolted into the sky.

The Russian-made rocket — flying in the Soyuz ST-B configuration — made its 11th launch from the European-run Guiana Space Center, carved from the frontier of the Amazon rainforest on South America’s northern coastline.

The Soyuz has logged more than 1,800 flights in many configurations since the dawn of the Space Age, and Friday’s launch from French Guiana was the workhorse rocket’s second flight of the day. Another Soyuz booster dispatched a three-man crew to the International Space Station hours earlier from the Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan.

The 15-story launcher tilted on a trajectory northeast from French Guiana, rocketed through clouds, surpassed the speed of sound and shed its four kerosene-fueled first stage boosters in the first two minutes of the mission.

A second stage core engine continued firing as the launcher jettisoned its 13.4-foot (4.1-meter) diameter nose cone, exposing the mission’s two Galileo satellite passengers to space. A third stage fitted with a modernized RD-0124 engine fired next, then the rocket’s Fregat upper stage took control of the mission.

The Fregat main engine was programmed to maneuver the satellites into a circular orbit 14,615 miles (23,522 kilometers) above Earth. The task took more than three hours, with two engine firings bridged by a lengthy unpowered coast.

The Fregat’s in-space maneuvers proved tricky on the most recent launch of Galileo satellites in August 2014, when fuel feeding the rocket stage’s attitude control thrusters froze after exposure to super-cold helium pressurization lines. The mishap left the Fregat pointing in the wrong direction during a critical orbital circularization burn, leaving the twin Galileo satellites in the wrong location in space.

Technicians implemented procedures to re-route the fuel plumbing on subsequent launches, and rockets with Fregat engines have functioned as designed on flights since the August failure.

The Fregat upper stage appeared to complete its mission successfully Friday, and officials announced the rocket placed the two European-built Galileo satellites — nicknamed “Adam” and “Anastasia” — into on-target orbits.

“I’m delighted to announce that according to our on-board telemetry system, ‘Adam’ and ‘Anastasia’ have been safely separated on their targeted medium Earth orbit,” said Stephane Israel, chairman and CEO of Arianespace, which manages Soyuz launches from French Guiana. “It’s a full success — a full success for Galileo tonight.”

Arianespace waited to more than an hour after separation of the satellites before declaring the flight a success. Officials prematurely celebrated after the bungled launch in August, only to learn later the mission ran into trouble.

“Tonight is very important for Arianespace because our raison d’être is to guarantee European governments and institutions independent, reliable and available access to space, and tonight we’ve carried out our mission,” Israel said in remarks after the launch. “So it’s a moment of great emotion because it’s the resumption of launches for the Galileo mission.”

The Galileo satellites each weigh about 1,574 pounds (714 kilograms) with a full load of propellant. The spacecraft will burn some of the fuel over the next few weeks to move into Plane B of the Galileo constellation.

“The satellites are doing fine,” said Didier Faivre, head of the European Space Agency’s navigation department. “They’re in good hands managed by the Toulouse CNES operational center. We have a perfect trajectory — at least the very first elements are extremely favorable.”

Ingo Engeln, a member of the executive board of OHB in Germany, which manufactured the Galileo satellites, said the new spacecraft had extended their power-generating solar panels and were aligned toward the sun to charge their batteries.

“It was very important for Europe that we should be successful tonight,” said Daniel Calleja Crespo, director general of the European Commission’s enterprise and industry directorate. “It was very important because the Galileo program was challenged, and tonight was a beautiful success … The quality of the satellites is excellent. The satellites are on the right orbit, so I think we made a decisive step forward in this program.”

The European Commission, the EU’s executive body, manages the Galileo program with technical assistance from ESA.

“Europe is building a strategic program that will contribute huge benefits, that will give us autonomous and independent access to space and will allow Europe to continue on the path of research and innovation to offer new opportunities to its young people,” Crespo said in a speech after Friday’s launch.

After initially speaking in French, Crespo switched to English: “With the success of this mission, Galileo is now irreversible.”

The navigation stations launched Friday aimed for the same slot in the Galileo fleet as the spacecraft stranded by the botched deployment last year.

Ground controllers salvaged the Galileo platforms that fell victim to the botched launch in August — known as Satellite No. 5 and No. 6 — by moving them into a quasi-circular orbit close enough to the rest of the fleet to be incorporated into the navigation system.

Faivre told reporters Friday that the satellites could become fully functional parts of the Galileo network by reprogramming ground systems to account for their irregular orbits.

The updates to the ground system are expected to cost less than 10 million euros, or about $10.8 million, Faivre said.

“We have now defined what has to be done,” Faivre said. “We have demonstrated with test tools that it works. We have to wait now for the operational constellation. It takes several months and costs a few million (euros), but that is nothing compared to the replacement of the satellites.

“For the majority of the users, these satellites should be considered as just another part of the constellation,” Faivre said.

The European Commission self-insured the satellites launched in August. The practice is typical for most government space missions in Europe and the United States.

Faivre said the program will procure insurance coverage for future Galileo satellites, beginning with the next mission later this year.

Galileo satellites will eventually fill three orbital pathways inclined at an angle of 55 degrees to the equator. Each plane will have 10 satellites when the constellation’s deployment is complete.

Friday’s launch carried up the seventh and eighth Galileo satellites, and the third and fourth members of the program’s Full Operational Capability phase. The European Commission has ordered 22 FOC satellites from OHB of Bremen, Germany.

Surrey Satellite Technology Ltd. of the United Kingdom supplies the L-band navigation payloads for the satellites.

Four satellites supplied by a separate industrial consortium launched in 2011 and 2012 to validate the operability of the Galileo system. The test spacecraft are now considered full-fledged members of the Galileo fleet, despite an issue with a navigation antenna on one of the satellites.

“This will (have) some consequences that will be applied in the future for these kind of navigation antennas, not only for Galileo but for other missions,” said Javier Benedicto, ESA’s Galileo program manager.

Benedicto said the other three In-Orbit Validation, or IOV, satellites are susceptible to the same glitch, and engineers are working on a software patch to allow ground controllers to identify the problem early if it appears on another spacecraft, potentially minimizing its effect.

After Friday’s liftoff, 18 Galileo satellites under contract remain to launch. Faivre said Galileo officials plan to purchase more spacecraft — either four or six — this year or next year to launch the entire 30-satellite fleet by 2020.

Faivre said production of Galileo satellites by OHB is proceeding apace. Crews then ship the satellites to ESA’s test center in the Netherlands for checks, before transporting them across the Atlantic Ocean to the Guiana Space Center.

Two more Galileo satellites are due for liftoff in September on a Soyuz rocket, followed by another Soyuz launch with a pair of navigation payloads at the end of 2015 or the beginning of 2016.

The first of at least three Galileo launches aboard larger Ariane 5 rockets could take off in 2016, Faivre said. The Ariane 5 can take up four satellites at a time.

When complete, the 30-satellite constellation — 24 active platforms and six spares — will beam navigation signals to users around the world. New receivers can accept data from GPS and Galileo satellites, offering members of the public improved accuracy in positioning and timing as the number of spacecraft in the sky grows over the coming years.

Managed by the European Commission with technical support from ESA, the 5.4-billion euro ($5.8 billion) Galileo system is billed as an independent network operated by civilians. The GPS satellites are owned by the U.S. Air Force and access to navigation data could be restricted in times of war or crisis.

European officials do not sell the Galileo system — one of Europe’s most costly space programs ever — as a rival to the American GPS network. The Galileo system is designed to be interoperable with GPS and Russia’s Glonass navigation satellites.

Working together, the GPS and Galileo satellites could offer the global population positioning information with an accuracy of just a few centimeters, an improvement from the several-meter error publicly available with GPS today.

The best GPS signals are reserved for military use, just as Galileo’s most accurate positioniong estimates will be regulated.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.