When night falls on Kibera, it is like a door slamming shut.

When the sun is up, things are hectic and loud, rough and fetid, but always safe and even welcoming: Bright colors abound and so do offers of nyama choma (roasted meat, usually goat) and bottles of Tusker, the local lager. Soon after the first stars appear in the sky, the streets of Nairobi, Kenya's largest urban slum go silent, emptying out but for dogs, cats and rats, thieves and rapists. Life moves indoors, and because most people are too scared to leave their homes to use outhouses and public latrines, "flying toilets" (plastic bags holding human waste) are tossed out of doorways and over fences into the streets.

One night this past October, the sobbing of a girl cut through the muffled music reverberating behind the tin walls of makeshift homes and businesses. Tracking the noise, a middle-aged man discovered a young woman slouched against the wall in an alley. Her face was contorted in pain, and blood had soaked her skirt and pooled around her body.

Acting quickly, the man ran through the streets until he found a wheelbarrow. He then lifted the woman—a girl, really—and placed her inside. More blood flowed from her body as he wheeled her to the Marie Stopes Kibera Clinic.

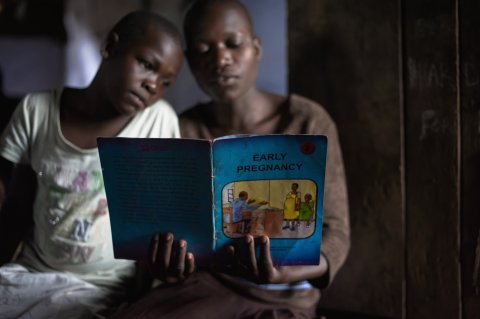

The next morning, Jimmy Ireri Njagi, manager of the clinic, found the girl on his doorstep, still in the wheelbarrow. Quickly, he diagnosed the problem: a botched, back-alley abortion. Within hours, he had her in a nearby hospital, where emergency health care workers operated on and saved Florence Akinyi's life.

"The pregnancy was an accident," says Akinyi, a pretty 18-year-old with a buzzed hairstyle and shy smile. She is so grateful to Doctor Jimmy (as everyone calls him) that she has become a sort of de facto office assistant, running small neighborhood errands and speaking with the young patients at the clinic.

Akinyi is one of the lucky ones. Too many more like her do not survive bad abortions, or suffer long-lasting health problems because of them. And then there's the even greater number of young women who, because they lack resources, keep unplanned children and end up trapped in a cycle of poverty and poor health.

It's an ancient problem, with a very obvious solution: give women full reproductive rights, including easy access to contraception and other family-planning options. Family planning and reproductive health are some of the most crucial tools for reducing human suffering in a changing and increasingly crowded world.

No Food, No Water

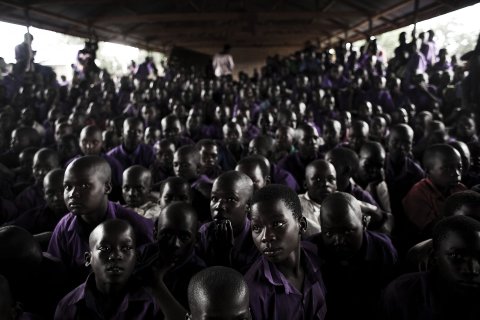

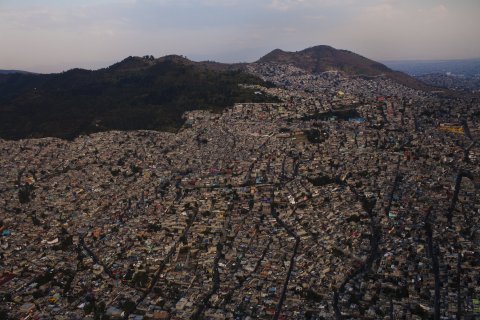

Like many Kibera residents, Akinyi moved to the city only recently—she arrived a year ago from "the upcountry." It's not clear how many people live in Kibera, but the Kenyan census says that at least 200,000 are crammed into this makeshift, two-square-mile shantytown. The impact of this massing of humans is like a physical blow: The land and city infrastructure can't keep up with the people. Step between the houses of Kibera and into a back alley and you are likely to come across gulches carved into the dirt by streams of wastewater, the ad hoc sewage system here, and garbage and waste piled high.

Kenya is in the midst of a population explosion. With a high fertility rate—the average Kenyan woman has 4.5 children, compared with 2.3 worldwide—Kenya's population of 44 million is projected to more than double to 97 million by 2050. Meanwhile, more than a quarter of Kenyan women are still unable to access the contraceptives they want. Despite over a century of family-planning aid work, it remains one of the most misunderstood aspects of international development. This is in large part because of Western efforts to apply a coercive form of population control under the guise of "family planning."

Globally, birth rates are lower today than ever, and more women than ever before are masters of their own bodies. But global populations are still on the rise, and in many parts of the world—Africa most prominently—the problems created by a lack of reproductive rights are getting more dire. In 1650, there were about 500 million people on Earth. By 1804, the population had doubled to 1 billion. In just 123 years, it doubled again, to 2 billion, and it doubled yet again, to 4 billion, by 1974. The world's population passed 7 billion in 2011. The latest U.N. projections suggest we'll be up to 12.3 billion by 2100, with no stabilization in sight.

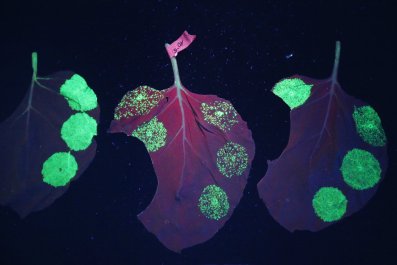

Meanwhile the rest of Earth's flora and fauna are being pushed aside. We are in the midst of the biggest mass-extinction event since the dinosaurs were obliterated 65 million years ago. A recent paper in Science found that plant and animal species are now going extinct at least 1,000 times faster than they did before humanity's arrival, due mostly to human-caused habitat destruction and climate change. Some scientists have taken to describing our current epoch as the Anthropocene, to highlight the fact that humans have irreversibly changed the ecological makeup of the planet.

In the 1970s, with the global population hovering around 4 billion, humanity began using more resources than the Earth could replenish each year, and was producing more waste than it could absorb, pushing us all deeper and deeper into "ecological overshoot," according to California think tank Global Footprint Network. It estimates that in 2014 humans used the resources of 1.5 Earths.

Most of the population growth is occurring in African nations. The continent hosts 15 percent of the world's people; by 2050, the U.N. projects, that number will be closer to 25 percent. This is particularly problematic, because much of the continent is also where people are less able to adapt to the effects of overpopulation, says John Wilmoth, director of the U.N. Population Division. If the world can't meet Africa's need for family planning, the result will be more and more poor, and poorly educated, people, he says. Kenya, Ethiopia and Malawi, for example, are three nations where large numbers of women can't get the contraception they need and are at high risk for climate change effects like flooding and drought.

As climate change turns more coasts into flood zones and more farmland to desert, the damage will be inextricably linked to population growth—the more of us there are, the more water, food and energy we'll need to survive. In the past three years, Australia, Canada, China, Russia and the U.S. have all suffered devastating floods and droughts that severely impaired food harvests. Earlier this year, the Food and Agriculture Organization said that to feed a population of 9 billion in 2050, the world must increase its food production by an average of 60 percent or else risk serious food shortages that could bring social unrest and civil wars. By comparison, wheat and rice production have grown at a rate of less than 1 percent for the past 20 years.

Mark Montgomery, a scholar at the Population Council, studies how the urban population boom will cause dramatic freshwater shortages. By 2050, the U.N. projects that 70 percent of the world's population will live in cities. Already, 150 million people in cities around the world suffer from freshwater shortages. In a recent paper, Montgomery and his colleagues found the number of urbanites with inadequate water will rise by more than 1 billion by 2050, and cities in certain regions "will struggle to find enough water for the needs of their residents."

The Big Taboo

Roger-Mark de Souza is fed up. The director of the population, environmental security and resilience arm of the Wilson Center, a government think tank in Washington, D.C., he says most of the discussion about adapting to climate change ignores the population explosion. "If you have all of these initiatives being put in place, and you have ongoing population growth, to what end?" he asks. "If we only invest in programs that do not take into account these broader social interventions, there is a missed opportunity."

The Green Climate Fund, perhaps the most high-profile fund helping developing countries adapt to climate change, does not say anything about population on its website. The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, which manages climate-focused "national adaptation programmes of action" for the least-developed countries, devotes a section of its website to the role gender plays in climate change. Women, it explains, are more vulnerable to its ravages and must be included in adaptation efforts. But family planning and contraception aren't on the official list of adaptation projects.

This failure has been exacerbated by the long and ugly history of wealthy, predominantly white powers manipulating family planning on the continent for several centuries. Europeans came to Africa "looking for bodies," says Nwando Achebe, a professor of history at Michigan State University. First was the slave trade. Then came the colonist era, when Europeans settled in Africa, establishing massive farms and plantations requiring local labor. Both groups of invaders "needed a population of able-bodied Africans," says Achebe. "They were enacting laws to make sure the population grew."

Columbia University history professor Matthew Connelly argues that the 20th century wasn filled with wrong-minded approaches to family planning that have ranged from using risky contraceptives on unwitting clients—in 1967 a Ford Foundation report praised a proposal for a new technology involving "an annual application of a contraceptive aerial mist" (from a single airplane over India)—to offering cash incentives to poor people who agreed to be sterilized. Policies like these "made family planning seem like an imposition, rather than something that served clients' own interests," writes Connelly, and the backlash was ferocious. Revolutionary leaders worldwide (including Daniel Ortega in Nicaragua and Zulfikar Ali Bhutto in Pakistan) attacked family planning as a symbol of American imperialism, and the Vatican jumped on board, helping organize a global campaign against family-planning efforts, which just happened to line up with the Catholic Church's official stance on procreation, particularly in developing countries.

In 1984, President Ronald Reagan instituted what has become known as the "global gag rule" (officially the Mexico City Policy), which stopped U.S. dollars from flowing to any international family-planning groups that provided abortions. The rule also stipulated that any organization receiving U.S. funding could not educate patients on abortion or take a stand against unsafe abortion. President Bill Clinton repealed the policy in 1993, George W. Bush reinstated it in 2001, and Barack Obama repealed it again in 2009. If a Republican takes the presidency in 2016, the gag rule will likely come back.

When the gag rule was in effect, United States Agency for International Development (USAID) funding to family-planning organizations plummeted. Clinics providing everything from condom distribution to HIV/AIDS treatment to neonatal care cut back their staff and services, and in some cases shuttered their doors entirely. In some cases, the rule backfired: Kelly Jones, a senior researcher at the International Food Policy Research Institute, found that in Ghana during gag rule periods, rural pregnancies increased by 12 percent and the rural abortion rate increased right along with it, going up by 2.3 percent.

Meanwhile, U.S. funding for family planning abroad has flatlined for several years, at about $530 million, although it would take relatively little money to make an enormous difference. For every dollar spent on family planning, USAID's website boasts, up to $6 is saved on health care, immunization, education and other services. Put another way, every dollar not spent on family planning will cost the U.S. up to $6 more in the long run. "It's not difficult to understand that contraceptive devices are relatively cheap compared to the cost of building roads and schools and hospitals," Wilmoth, the head of the U.N. Population Division, says. "So it's not for lack of money that it isn't accomplished."

While the West waffles on providing aid for family planning, "Africans are asking for [it]," says Faustina Fynn-Nyame, Marie Stopes's country director for Kenya, who is from Ghana. "Africans see the importance of this. It's not the West telling us to do something."

Leaving Half the Population Behind

In 2012, the estimated number of unintended pregnancies was 80 million (63 million in the developing world). World population growth? Also 80 million. In other words, if women all over the world had the ability to prevent the pregnancies they don't want, the world's population would stabilize.

That would immediately improve both maternal and infant health. In most parts of the global south, access to abortion is either extremely limited or prohibited. In Kenya, a nurse was sentenced to death for providing abortions this past September. Any pregnancy terminations in Nairobi have to be done on the backstreets, often using DIY drugs made by chemists more concerned with sales than efficacy, says Njagi, the Marie Stopes clinic manager. That's how Florence Akinyi ended up nearly bleeding to death in a wheelbarrow.

Worldwide, it's estimated that 20 million women have unsafe abortions every year because they lack better options. Over 5 million of them end up needing urgent medical attention, and 47,000 die in the process. In addition, in the developing world pregnancies are often dangerous. Every year, an estimated 358,000 women die during childbirth, and many more suffer debilitating pregnancy-related health problems. In sub-Saharan Africa, the lifetime risk of dying from pregnancy-related problems is 1 in 22. Lower pregnancy rates and you lower those risks—fewer pregnancies means resources don't have to be spread dangerously thin.

Since 2011, the United Nations Population Fund (working to "ensure universal access to reproductive health, including family planning") has been led by Dr. Babatunde Osotimehin, a Nigerian national. At the U.N. General Assembly meeting in September, Osotimehin urged the group to focus on gender equality. "We cannot advance by leaving half of the population—our women and girls—behind," he said. At the same meeting, Bathabile Dlamini, a representative of South Africa, said her country had recently implemented policies allowing access to safe abortion services and had seen an increase in life expectancy from 54 in 2005 to 60 in 2011.

Of course, abortion is the last resort; it's far better to help women before conception. According to research from the Guttmacher Institute, 39 percent of all pregnancies in sub-Saharan Africa—an estimated 19 million—were unintended in 2012. Of those 19 million, the institute estimates 10 million resulted in unplanned births, 3 million in miscarriages and 6 million in abortions, most performed in unsafe conditions. Providing access to contraception for every woman in sub-Saharan Africa who wanted it might prevent 5 million abortions and save the lives of 48,000 women. What's more, 555,000 fewer newborns and infants would die, cutting infant mortality in the region by 22 percent.

Many Kenyan women would like to have power over how many children they have, and when. "We have a high unmet need," says Fynn-Nyame, adding that "20.9 percent of married women say they want to control their fertility somehow but don't have the access, money or awareness of where to go."

In the developing world, 222 million women want contraceptives but can't get them. (That is more than the population of Germany, France, Belgium, Spain and the Netherlands combined, notes a video by Population Action International.) Meeting their needs would have prevented 54 million unwanted pregnancies, 26 million abortions, 79,000 deaths of mothers in pregnancy or childbirth and 1.1 million infant deaths in 2012 alone.

Plus, contraceptives let women space out births, leading to far healthier children. If all families in the developing world put a three-year gap between pregnancies, almost 2 million fewer children under 5 would die each year, according to research from the USAID.

The problem is that too many of these important decisions are taken out of women's hands. Over 10 percent of Kenyan women report being raped by their partners. "Women have very little power when they are having sex within their marriage," says Fynn-Nyame. A woman might know that she's at a fertile point in her menstrual cycle, but she won't be able to negotiate with her husband. If he wants sex, she has to give in.

Fynn-Nyame says a lot of the work her team does is with men. It works, she says, particularly among young men. The problem is that misinformation about contraceptives is so endemic that even men who want to participate in family planning either don't know how or don't have the access. For example, recent research shows that young Kenyan men in universities will often have a glass of water and the morning-after pill ready for their date to take before sex. It's effective—though not exactly healthy for the woman who takes it. But "what else are you going to do?" asks Fynn-Nyame. "You want to finish your education and have a different life—you have all these dreams and aspirations."

'God Will Provide'

Achebe's first name, Nwando, is a shortened version of Nwabundo, an Igbo word that translates roughly to "a child is the shade." She says, "It means as the youngest daughter, I'm expected to stay with my parents as they grow old and shade them as a tree. Let my lineage not end. Let my path not close. These are names that Africans give their kids."

In much of the developing world, there remains a deep-seated imperative to have as many children as possible. In part, this is due to the pernicious influence of colonialists and missionaries, but it also stems from many decades ago, when child mortality was so high that if you wanted to have a few kids, you had no choice but to follow one pregnancy with the next. This is particularly the case among people who live off of subsistence farming in the rural areas, who feel that "the more hands we have, the more work we can do, and the more money we can take in," says Fynn-Nyame. Children are also considered an investment for a parent's old age. After all, if you have eight children, there's a chance at least one will have the wherewithal to care of you when you grow too old to care for yourself. And it doesn't matter if you can't afford eight children right now. "If you ask people whether they can afford these children," says Achebe, "the answer is always, 'God will provide.'"

Meanwhile, too many children lack information about sex and procreation. Many of the women in the Marie Stopes Kibera clinic come alone, with no real knowledge of their options. Often they will have been told by their husband what contraceptive to ask for—usually they are told to avoid intrauterine devices (IUDs) because it "makes sex less fun," says Njagi. "I try to teach them about their options so they can make a more informed decision."

And that might just be IUDs, which are one of the best forms of birth control—they have a failure rate of less than 1 percent, while birth control pills have a failure rate of between 8 and 9 percent. Plus, in regions where the health care infrastructure is shoddy, relying on a daily supply only drives up failure rates. As Elaine Lissner, director of the Male Contraception Information Project, puts it, "If you're somewhere on the pill and the pill truck doesn't show up one month, you're pregnant."

The Great Girl Bounce

What would happen if contraception suddenly became a universal right?

It did, in Bangladesh, which is seasonally flooded from Himalayan ice melt and is regularly bombarded by cyclones. The rising sea level, driven by climate change, is projected to wipe out 17 percent of its landmass by 2050 and displace 18 million people.

In the 1970s, Bangladesh, freshly independent, concluded it was growing too quickly—it was on pace to nearly triple its size in four decades. Women on average gave birth to more than six children. So the government made contraception free and distributed it widely.

In 1975, 8 percent of Bangladeshi women used contraception. By 2010, the number was over 60 percent. At the same time, educational opportunities increased: More than 90 percent of girls enrolled in primary school in 2005. Just five years earlier, female enrollment was half that number, according to The Economist. Women's literacy hit 78 percent in 2010, compared with just 27 percent in 1981. Women who had an average of six children in the 1970s have roughly 2.2 children today. That fertility rate is well below India's and far lower than Pakistan's. Bangladesh is now the only developing country on track to meet the Millennium Development Goals for child and maternal health.

"This is not just a medical issue; it is a social issue as well," the U.N.'s Wilmoth says. "The Bangladesh program did that community by community, with these women who would talk to people. It's amazing that [the fertility rate] has fallen that low in a country so poor. It's an example of what's possible."

The "Iranian miracle" is another example. It was the steepest population drop ever recorded—faster even than China's one-child policy. And it came without coercion.

In the late 1980s, Iran's Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini reversed a pro-natal policy meant to produce soldiers for the war against Iraq. Persuaded that the Iranian economy could not handle the bloated population, he issued fatwas making contraception available for free at government clinics. State-run TV broadcast information about birth control, and health workers educated patients on family planning as a means to leave more time between births. The fertility rate fell from seven births per woman in 1966 to fewer than two today. The plunging birth rate, coupled with increasing public education for girls, shifted the role of women in Iran. More women postponed childbirth to attend college, and now the country's universities are 60 percent female.

But in 2006 the-President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad attempted to halt the decline, calling the family-planning programs a "prescription for extinction," according to the Los Angeles Times. He urged Iranian girls to marry young, offered cash incentives per child, and thegovernment recently outlawed permanent surgical contraception. But it hasn't worked. "Iranian women are not going back," Sussan Tahmasebi, an Iranian women's rights leader, told the Times.

When women can have fewer children further apart, the effect on their lives is dramatic and immediate. They have more time to pursue education and get jobs, earning money that they are more likely to invest back into their family and community than their male counterparts do. They lead healthier lives and have healthier children. The power dynamic between men and women can change too: Women with more access to resources are less frequently victims of domestic violence, according to USAID.

The Aspen Institute estimates that if all women globally had access to the contraceptives they want, the reduction in unwanted pregnancies would translate into an 8 to 15 percent reduction in global carbon emissions. Fewer people would be in harm's way as sea levels rise and farmland dries out, and less pressure on resources already stretched thin would mean less violent conflict over those resources.

Out of Control

Not all experts agree that better family planning will save the planet. Connelly argues that the environmentalist argument for population control is at best wrong, and at worst disingenuous. "An individual human who is a subsistence farmer consumes about as many calories as a dolphin," he says. "You and me are consuming calories equivalent to a blue whale. One American blue whale is worth dozens of Bangladeshi dolphins. To say 'if only there were fewer dolphins, the rest of us whales would be OK' I think is crazy. And it's a cop-out. And it's unfair."

The point he is making is that the real problem for the planet is overall consumption. In some family-planning clinics, he says, there are posters on the wall depicting two families: the unhappy, unplanned family, living in abject poverty and violence, and the happy, planned family, with a suburban home and two cars parked in the driveway. The idea it promotes is "the miracle of family planning: If you get rid of the kids, you can have more stuff."

But, he adds, "you can't have it both ways. Either we're going to lift hundreds of millions and eventually billions of people out of poverty and make them consumers of cars and everything else, or we're going to reduce numbers of people so they will consume less. How do you reconcile these two things?"

Nevertheless, even if family planning won't solve our resource challenges, Connelly says, there is no doubt the world would be a better place if women and families everywhere had access to their full reproductive rights. And the demand for contraception is there. In Kenya, Fynn-Nyame sees it. "When you speak to these women, they are very angry, but at the same time, if they had different choices in life, if they knew earlier, they wouldn't [have] wanted to have so many children, because they're worried about the future of their children. They're worried about food security, they're worried about education. If they get pregnant again and they die, what's going to happen to their children?" she asks. "Her survival is so crucial, but her ability to survive is all based on whether she can get some sort of fertility control."