- India

- International

The appeal of the problem solver

Modi is a seasoned politician but the rising tide of expectation poses a big challenge to his popularity.

Modi’s ability to sway the electorate is linked to the fact that in weakly institutionalised states, individuals can exercise a large influence.

Modi’s ability to sway the electorate is linked to the fact that in weakly institutionalised states, individuals can exercise a large influence.

There is an overwhelming consensus that it is not the BJP, but its prime ministerial candidate Narendra Modi, who won the 2014 Lok Sabha elections for the party. This is not misplaced. The National Election Study (NES) 2014 data suggest that approximately one in every four BJP voters would not have voted for the party had Modi not been the party’s PM candidate.

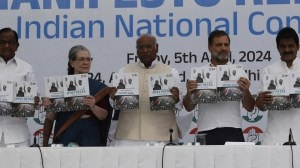

The contrasting image of Modi as an efficient administrator and powerful orator in comparison to the incumbent Manmohan Singh and Congress leader Rahul Gandhi during the campaign lends credence to the idea that Modi’s leadership swung the election results in the BJP’s favour. The NES 2014 also confirm that Modi’s popularity cut across large parts of the social and political landscape of India.

The 2014 elections were not the first with leadership proving to be a huge factor in attracting voters. Earlier elections in India have also centred on leaders like Jawaharlal Nehru, Indira Gandhi and Atal Bihari Vajpayee. However, the effect of leadership on influencing election outcomes raises a significant, and yet unexplored, dimension of Indian politics. Why should the prime ministerial candidate matter to a daily wage labourer in a rural district in central India?

The effect of leadership is often attributed to charismatic personalities who inspire large swathes of people. Among prime ministers in independent India, most would associate Nehru with a charismatic personality, and some may see Indira Gandhi and Vajpayee as charismatic to an extent. Though he may become one in years to come, Modi at present does not fit the bill of a charismatic leader who could inspire the masses. How then did he attract a large share of the electorate?

There are two plausible explanations for leadership playing such a big role in influencing election outcomes — cultural and institutional. First, leadership is embedded culturally in Indian society, where people look to individuals to sort out their problems. The leader appears in popular perception as a problem-solver, one who could set everything right. The popular imagery of the “angry young man” in Bollywood movies, N.T. Rama Rao (later chief minister of Andhra Pradesh) in Telugu movies or M.G. Ramachandran (later chief minister of Tamil Nadu) in Tamil movies is all too common, where an individual takes the law into her hands to set the system right.

The second reason for the significance of leaders is structural. In polities such as India, where the rules governing the system are arbitrary and opaque, individual leaders become important. Political parties in India are weakly institutionalised and often centred around a leader or a family. Within political parties, the leader’s authority is frequently unquestioned. The leader is often the party (almost all regional parties in India are the domain of individuals or families).

The leader can also symbolise a party’s programmes and policies. Examples abound. For instance, there is little distinction between what the party stands for and its leader in many states, including but not limited to Lalu Prasad in Bihar, Mulayam Singh Yadav in Uttar Pradesh and J. Jayalalithaa in Tamil Nadu. This phenomenon is present in other parts of the world as well, where parties and leaders are often inseparable.

Leadership in India becomes more important because India’s political system is marred by administrative inefficiency and arbitrariness. Ordinary citizens find it hard to get legitimate concerns addressed. So they look up to individuals who would bypass rules to get work done. As Anirudh Krishna of Duke University puts it, the interaction with the Indian state (where the rules of the game are unclear) is an expensive affair for ordinary citizens, as pahunch and poochh is all that matters. For ordinary citizens, pahunch relates to individuals one knows or can reach and poochh is an appeal made to an individual who can set things right for a supplicant.

This is exactly the image Modi portrayed. He presented himself as a problem-solver — an efficient administrator who could make things happen. This image is consistent with what citizens seek in a politician. In a 2002 survey on representation carried out by the Centre for the Study of Developing Societies, citizens were asked about the qualities they sought in politicians. One quarter of the respondents said that a politician should be a problem-solver. An equal proportion wanted an honest politician. Less than 10 per cent looked to a politician to provide public goods.

The presentation of Modi as a leader who could make things happen resonates more with the electorate than the Congress’s presentation of its leaders as those who are more inclusive. The India Today-Cicero group post-poll survey conducted an experiment on whether citizens preferred a leader who was more decisive or inclusive. Citizens were randomly assigned to answer one of two questions. One question asked whether they agreed with the statement that India needed a leader who makes firm and quick decisions. The second asked respondents whether they agreed that India needs a leader who was inclusive and took everyone along, even if that meant decision-making would be slower. Eighty-four per cent of those who were randomly assigned the first question agreed that India needed a decisive leader. In contrast, only 68 per cent of those assigned the second question — that is, if India needed a more inclusive leader — were likely to agree with it.

Similar patterns can be seen in the first tracker poll (July, 2013) conducted by Lokniti-CSDS. In that survey, respondents were asked what characteristics they sought in their leaders. Separately, citizens were asked whom they would prefer as prime minister — Rahul Gandhi or Narendra Modi. Among those who preferred Modi as PM, decisiveness and experience were rated as the most preferred leadership quality. On the other characteristics of a leader, such as honesty and inclusiveness, there was no difference between Rahul Gandhi and Modi.

Modi did have a decisive impact on this election, but this was not due to charismatic qualities associated with him. His ability to sway the electorate is directly linked to the fact that, in weakly institutionalised states, individuals can have

a large influence.

Charismatic appeals take longer and bigger blunders to erode, whereas the image of a problem-solver starts fading quickly when the leader fails to live up to expectations. Arvind Kejriwal’s declining fortune is an example. Modi is no Kejriwal. Modi is a seasoned politician, one who rose from below to the top position, but the rising tide of expectation that he will miraculously reform the system and get things done poses the biggest challenge to his popularity.

Now in power, Modi alone cannot bring all the changes he wants. His success in maintaining the image of the problem-solver will also depend on how ministers, parliamentarians and bureaucrats perform. Vested interests in Lutyens’ Delhi have their own way of killing problem-solvers softly.

The writers are with Lokniti-CSDS, Delhi and the Travers Department of Political Science, University of California, Berkeley, US.

EXPRESS OPINION

More Explained

Apr 25: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05