The last time the Commonwealth Games came to Scotland, in Edinburgh in 1986, the cast list of champions was mightily impressive. Steve Ovett left the 800m and 1500m to Steve Cram, and ran instead in the 5,000m, which he duly won. Daley Thompson won the decathlon for the third time in a row, while Linford Christie was beaten in the 100m by Ben Johnson. Steve Redgrave took three rowing golds, and the first-time winners included Sally Gunnell and Liz Lynch, who would be a world champion as Liz McColgan. And then there was Lennox Lewis, whose victory in the newly introduced super-heavyweight class summed up all that was wrong with those Games.

When the BBC cameras focused in on Aneurin Evans, Lewis’s opponent in the final, the most famous voice in British boxing said, “He really is out of his depth here. If I were him I’d be running for my life.” Perhaps Evans heard the remark by the great commentator Harry Carpenter, for he spent the next few minutes trying, unsuccessfully, to evade Lewis’s brutal punches. Evans’ corner threw in the towel after 23 seconds of round two. The title went to Lewis, the best boxer to have fought in the Commonwealth Games. And the young Welshman Evans became the unlikeliest silver medallist.

Two days before the Games a late plea went out for more boxers: there were only two entries in the super-heavyweights, Lewis and the Englishman James Oyebola, who had beaten Evans earlier in the year. A mass boycott of the Games, led by African countries, hurt boxing more than any other sport: Nigeria, Ghana, Kenya, Uganda and Zambia all had strong contenders who stayed at home.

Wales nominated Evans, whose luck was in. He zipped up to Scotland and drew a bye into the final. Lewis, representing Canada before his later switch to Britain, where he had spent most of his childhood, made short work of Oyebola first, then pounded Evans into submission.

But for a rule change during the Games, Evans might still not have been on the podium. All three medals could not be awarded unless there was a minimum entry of five individuals in any contest – but because of the “special circumstances” of the boycott, the Commonwealth nations voted halfway through the Games to award three medals regardless of the entries. Lewis went on to world fame, Evans returned to obscurity in Caerphilly.

The biggest hero for the Scottish crowds was, by some distance, Liz Lynch, who was on the dole when she won the 10,000m. It was the first time the distance was contested by women at the Commonwealth Games; it was Scotland’s only gold medal in athletics. Two of Lynch’s fellow runners had bet her £75 that she would cry at the medal ceremony. She lost. “I didn’t think I would, but the crowd were something else and Scotland the Brave sounded so wonderful. It was so overwhelming, totally unbelievable. I could never, ever relive that moment.”

The undisputed champion of headline-making at Edinburgh 1986 was none of those medallists, though. It was a Jewish Czech war hero whose mother died in Auschwitz; a self-educated son of a peasant farmer who spoke 10 languages. He made a fortune from publishing, allegedly helped along by Britain’s secret service, was an MP for six years but was “not a person to be relied upon to exercise proper stewardship of a publicly quoted company” according to the Department of Trade, who investigated his dealings. He owned the world’s largest scientific and educational publishing company, Mirror Group Newspapers, two football clubs, and a massive ego. Lampooned in the satirical magazine Private Eye as “Cap’n Bob”, he craved international status as a political figure. He was born Jan Ludvik Hoch: he was better known as Robert Maxwell.

These were the most bizarre, most troubled Commonwealth Games ever staged. A few weeks before the opening ceremony there had been talk of crisis, even of cancellation. More than half of all Commonwealth nations stayed away, as did the much-needed sponsors who might have kept Edinburgh out of debt. If Margaret Thatcher was the villain – there was no shortage of people keen to cast her in that role – then Maxwell claimed to be the hero. The Press called him “the white knight” when, with five weeks to go to the opening ceremony, Mirror Group Newspapers became the main backers and he took over as chairman of the company running the Games.

Maxwell himself said he was “the saviour”. He hinted as much to the Queen when, much to his delight, he was introduced to her in Edinburgh by his personal photographer and aide Mike Maloney, who had been on many royal assignments. Maxwell handed the Queen a gift of a set of coins in a magnificent display box, and said, “Permit me to present you with a token of this great event that I have orchestrated.”

People were still arguing about Maxwell’s role nearly three years later when the last of the bills was finally paid, though not by him. His name was still being discussed in the late summer of 1998 when the company in charge, Commonwealth Games 1986 (Scotland) Ltd, held its final meeting. By then the “white knight” was long dead, his name blackened forever. In November 1991 Maxwell went overboard from his private yacht in the Mediterranean. It became clear after his death that he had fraudulently misspent hundreds of millions of pounds from his employees’ pension funds.

Without him, though, Edinburgh 1986 would have been an embarrassment that Scotland, Britain and the Commonwealth Games Federation might never have lived down. The Games would also have been a good deal less colourful without Maxwell, who liked to do things differently. On one occasion he invited a number of VIPs and their partners to dinner at his private suite. He served them Kentucky Fried Chicken straight from the bucket.

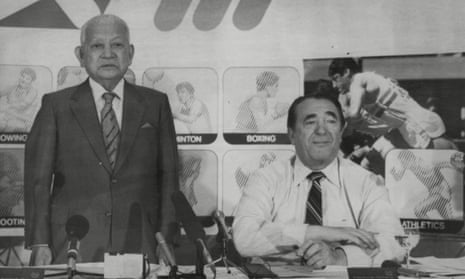

At another function he introduced his friend Ryoichi Sasakawa to the press. He announced the Japanese businessman, who pumped in far more money than Maxwell himself, as a multimillionaire philanthropist who had “single-handedly funded the eradication of leprosy”. That claim was strange enough, given that more than 200,000 were still suffering from the disease a quarter of a century later, but Sasakawa himself left reporters even more dumbfounded when he told them that he was 27 years old and would live to the age of 200. He was 87 at the time.

Why did Maxwell get involved? Maloney believes that somebody made a speculative suggestion to him about backing the Games, and he suddenly saw a great opportunity. “He thought he could be the saviour, and he was,” said Maloney, who was with Maxwell for his six-week involvement in Edinburgh.

What a difference from Edinburgh 1970 when, for the first time, the event had been tagged “the Friendly Games”. The overall budget was £3m; in 1986 it was £17m.

The spectre of a boycott was there from the start. The 1976 Olympics in Montreal, which cost the city a fortune, had lost 26 African nations who refused to compete because New Zealand were there. The problem was rugby: New Zealand’s All Blacks, like British teams, were still happy to play against South Africa at a time when other sports, supported by the United Nations, shunned them because of apartheid. The Soviet Union’s invasion of Afghanistan in 1979 led to another boycott, masterminded by the United States, of the 1980 Moscow Games. Within a few years sport had become a prime target for politicians.

Peter Heatly, later knighted for services to sport, had first suggested Edinburgh should bid for a second time. He was a diver, three times a gold medallist at the Games in the 1950s, who became a sports administrator and eventually the top man in the Commonwealth Games Federation. He recalled that talk of a boycott had always been around, “but when it hit, the extent and range surprised everybody. It broke 10 days before the Games and every morning you would wake up and another country had decided not to come. It was terrible. You died a little bit every day over those 10 days”.

In Unfriendly Games, a book that detailed all the pitfalls and problems of Edinburgh ’86, the authors concluded that the Games might never have taken place had Heatly not persuaded Edinburgh to put their name forward. No other city made a bid.

There had been a giant leap forward in sport, or at least in the commercialisation of it, in 1984. Despite a retaliatory boycott by the Communist countries the Los Angeles Olympics made a huge profit, through advertising and sponsorship deals negotiated by sharp businessmen. The Americans had shown the way: now the Scots could bring in sponsorship money too. They failed dismally. They needed professionals to negotiate deals, but relied on amateurs. Selling “the Friendly Games” to sponsors was beyond them, hence the late call to Maxwell.

On 10 July, two weeks before the Games were due to start, newspapers across the world ran reports from press agencies in London: Two black African nations, Nigeria and Ghana, announced yesterday that they will boycott the 1986 Commonwealth Games later this month in protest of Britain’s refusal to agree to major economic sanctions against South Africa.

The boycott appeared to be an attempt to put pressure on prime minister Margaret Thatcher, who has long opposed economic sanctions. The Nigerian Embassy in London said yesterday that the boycott was meant to “dramatise to the British government how strongly we feel about the matter”.

The final loss was devastating: 32 teams and nearly 1,500 athletes stayed away.

The massive success of the 1984 Olympics was largely down to one businessman, Peter Ueberroth. When he took over the running of the LA Games he created a committee of 150 “movers and shakers” to generate ideas. He persuaded Coca-Cola and other sponsors to back the Games despite worries over the economy and the Soviet-led boycott. The Olympics produced a profit of a quarter of a billion dollars. Ueberroth is said to be worth $100m.

In the same role in Edinburgh was Kenneth Borthwick, a confectioner and Conservative councillor who was Lord Provost of the city from 1977 to 1980. Alex Wood, then the leader of Edinburgh Council, was not impressed. “Borthwick was an old-fashioned small businessman, a conservative Conservative. Dithering inaction was his default position.”

Malcolm Beattie, the commercial figurehead of the Auckland 1990 Games and a leading name in New Zealand sports sponsorship, was more forthright. “Ken Borthwick was very old-school. He showed great deference to the Queen and the establishment but he didn’t understand anything about running a big sports event. We wanted to know about money, accommodation, sponsors – all he spoke about was the sound of bagpipes at dawn. The whole team were a bunch of amateurs.”

Edinburgh’s pride at becoming the first city to stage the Games a second time “turned to humiliation”, wrote Bateman and Douglas, when Maxwell had to be called in. One of his first pronouncements was that the early preparations had been “appallingly amateurish”.

No teams had withdrawn when Maxwell took over as chairman on 19 June. In the final fortnight before the opening ceremony, one after another, nations withdrew. Eight teams arrived and checked in to the athletes’ village only to discover that their governments had joined the boycott. Bermuda even took part in the opening ceremony before the athletes were ordered not to compete. “Have a thought,” said Maxwell, “for the hundreds of athletes who will be suffering heartache and disappointment that all their years of preparation have been wasted.”

At least Maxwell had made an immediate impact when he took over. He put newspaper owners and editors on media committees in London and Edinburgh, thereby ensuring favourable coverage throughout the country. He played a brilliant game, gaining millions of pounds worth of positive publicity. Logos for the Mirror and its Scottish sister paper, the Record, were everywhere – on the replay screen, on top of the main stadium scoreboard, the swimming scoreboard, at the diving pool, on the corner posts on the boxing ring. Officially the Games’ main sponsors were Guinness. In reality it appeared to be Mirror Group.

The accountants Coopers and Lybrand totted up all that exposure and put a value on it: £4.3m. By the final reckoning Maxwell had not even paid £0.3m. “No one could guess at the time that the White Knight would ride off into the sunset leaving a £3.8m debt behind for someone else to pay,” said his photographer-aide Maloney. “He got worldwide publicity, which was his main aim. Even so, he was the saviour of the Games, and he loved it.

“That whole time in Edinburgh was utterly unreal. As soon as he arrived he just took over. He was always at meetings, and whatever the subject, even if he knew nothing about it, he’d take control. On one occasion he came out of a meeting and wanted to go back to the hotel. He walked into the road and flagged down an official Games car and told the driver, ‘Take me to the Sheraton.’ The driver said he couldn’t, as he was due to pick up somebody else, but Bob said, ‘I’m Robert Maxwell and I shall give you a letter of absolution to present to your boss.’ He even dictated it to me in the car.

“Bob was a unique character. We became quite close friends but I have to say he was a bit of a pig when it came to eating.” On one occasion Maxwell ordered a banquet for 14 people from Edinburgh’s top Chinese restaurant. “There was plenty of Dom Perignon too,” said Maloney. “When he said ‘Tuck in,’ I asked if we shouldn’t wait for the other guests. There weren’t any – there was enough food for another 12 people and he just got stuck in, sometimes with his fingers. There was curry sauce dripping down his shirt-front when he went off to bed.

“When he served the Kentucky Fried Chicken at another reception, it wasn’t the first time. He would do it at the Labour party conference too. When he was offering round the buckets he actually took a bite out of a leg and said to one of the lady guests, ‘Tastes good, try this - you’ll like it.’ And he put the chicken leg back in the bucket.”

Clearly, Maxwell liked his food. Did he enjoy the sport, too? “He didn’t have the attention span for that,” said Maloney. “Even at football matches he’d always invent an excuse to leave, pretending he had to make a call. He could never have sat through the 5,000m race, for example – far too long. The 100m would have been about his limit.”

Maxwell’s preferred setting was not the stadium; it was in front of the cameras. On the penultimate day of competition Maxwell called a press conference that was rated by some – among them Ian Wooldridge of the Daily Mail – as the strangest they ever attended. Maxwell welcomed Sasakawa, who would take questions through an interpreter. He was introduced as “a former politician who played an important role in the economic revival of his country after the war”. He had devoted himself to “world philanthropy”, and was president of the Federation of World Volunteer Firemen’s Associations, the World Union of Karate, the Japan Science Society and other bodies. Sasakawa spoke for five minutes, in Japanese, to explain what he was doing for world harmony.

Maxwell had glossed over some facts about Sasakawa. Yes, he had given away $12bn over 20 years, but no, he had not made his fortune from shipbuilding. A better picture of the man came after his death in 1995 – he did not quite make it to 200 – in an obituary in the Independent that said Sasakawa had been “the last of Japan’s A-class war criminals who stood out as a monster of egotism, greed, ruthless ambition, and political deviousness”. He claimed to have slept with 500 women, was said to have had links with the CIA, and was allegedly involved in the opium trade. He made his fortune from gambling and built a business empire worth billions. His donation to the Edinburgh Games was £1.265m.

The final deficit for Edinburgh ’86, before Sasakawa’s donation, was about the same as it had been before Maxwell took over – nearly £4m. The money from Japan made a big difference. Maxwell further reduced the losses by negotiation with creditors, among them two local councils. The Games’ administrative company did not clear up all its most pressing paperwork until 1989. There were still rumblings 10 years after that.

Was it all worth it? In Alex Wood’s opinion, no. His “very personal perspective, reached retrospectively” was that the city should never have been involved. “Robert Maxwell was a man of monstrous ego, devoid of any desire to serve the greater good.” Those on Edinburgh Council, both Conservative and Labour, who pushed “promoting the city” as a good reason for hosting the Games were more interested, in reality, in foreign trips and socialising with the rich and powerful. “My view is that Edinburgh should never have become embroiled in seeking to host the Games,” said Wood.

Despite all the failings and embarrassments, the Commonwealth Games Federation will be forever grateful that they did. Had there been no Games in 1986, who knows whether they would have made it back to Scotland in 2014?

Brian Oliver is a former sports editor of the Observer. This is an edited extract from his book, The Commonwealth Games: Extraordinary Stories Behind The Medals, published by Bloomsbury and priced £12.99

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion