As part of mammoth celebrations of the 200th anniversary of Norway’s constitution, the government is funding two artists to re-enact a "human zoo", which will open to the public on 15 May.

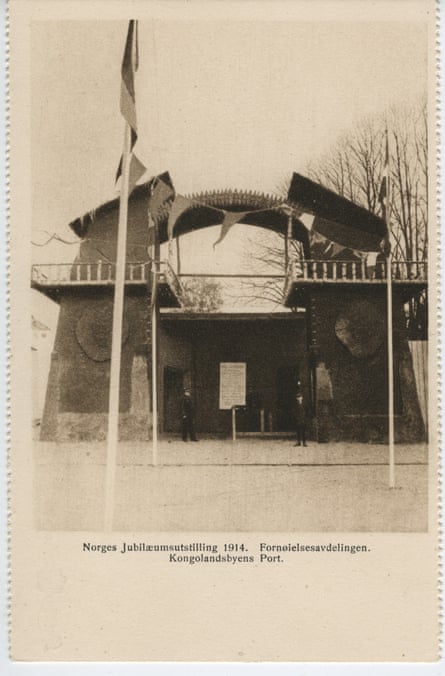

Oslo’s original human zoo or Kongolandsbyen was central to Norway’s world fair in 1914. The artists claim that the new project, which they named European Attraction Limited, is meant to provoke a discussion on colonialism and racism in a post-modern world, engaging with Norway’s racist past in the process.

Some anti-racism organisations and commentators have labelled the project offensive and racist. Is there any artistic value in the re-enactment of such a dehumanising spectacle, especially in a world not yet fully healed of racism? Is this an abuse of art? Or will the re-enactment reverse the modest gains of the equality struggles, especially when the world engages with the subject of race so superficially?

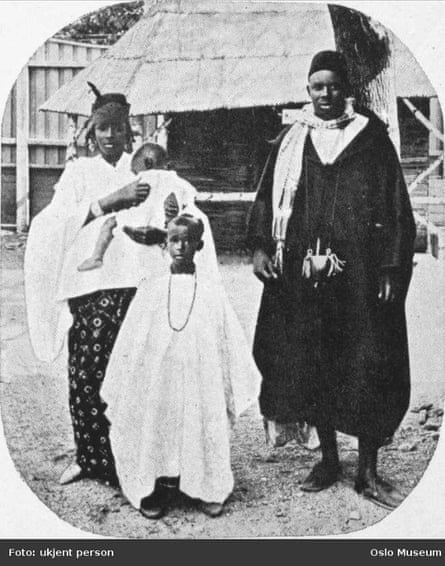

Norway’s 1914 human zoo is not the most widely known historical fact in the country, or elsewhere. But, for five months, 80 people of African origin (Senegalese) lived in "the Congo village" in Oslo, surrounded by "indigenous African artefacts".

More than half of the Norwegian population at the time paid to visit the exhibition and gawp at the "traditionally dressed Africans", living in palm-roof cabins and going about their daily routine of cooking, eating and making handicrafts. The king of Norway officiated at the opening of the exhibition.

There were several human zoos or "colonial exhibitions" in Belgium, Germany, France, the US and other western countries at the time, exhibiting Africans and other non-western peoples. These helped to convince the European public opinion of the necessity of colonisation. Exhibiting Africans as animals, uncivilised, primitive and animistic made it seem justifiable to colonise them.

It was also a source of entertainment for the European of the time to see how "backward" Africans were. Indeed after the Norwegian show, one Norwegian magazine, Urd, concluded: “It’s wonderful that we are white”.

In Belgium, some of the 267 Congolese being exhibited died during the show and were unceremoniously buried in an anonymous common grave. The whole spectacle denied Africans their dignity. They were treated as animals. The zoos reinforced the self-congratulatory mood prevalent in Europe at the time, considering itself the most advanced society in the world and "othering" the rest.

Artists Mohamed Ali Fadlabi and Lars Cuzner say that the ignorance around Norway’s racist past inspired them to re-create the human zoo for the 200th anniversary in May. They are said to have secured almost a million Norwegian kroner (£99,000) to implement the project. Volunteers are invited from around the world to come and populate the human zoo, but are warned that they will have to defend their participation against a hostile response.

The artists argue that the project is part of an honest conversation about race and Norway’s unpleasant past. They held a conference in February, in which they featured talks about systematic racism entitled The Terrible Beauty of Hindsight and The Origins of the Regime of Goodness. They legitimately ask: “How do we confront a neglected aspect of the past that still contributes to our present?”

Muauke B Munfocol, who lives in Norway and is originally from DRC, thinks that the project does not recognise the “racial order and systems of privilege in the country”. She says: “One might wonder why at such a time, rather than putting its efforts to acknowledge the existence of racism, paying reparations, and changing the historical-political and cultural relationship to other non-white countries, the Norwegian government chooses to finance a project that reaffirms their part in a global white domination system where black people are dehumanised spiritually, economically, socially and culturally.”

Muauke’s argument is that the re-enactment of the human zoo as exactly as how it was presented in 1914 means “a re-enactment of the fantasies about exoticism and bestiality that have been historically linked to the black body in the colonial mind”. The re-enactment will be a living reality for her, as an African living in Norway.

“Once again, the black body will be prepped, scripted and presented to a white gaze. Africans will once again be subjected to a humiliating and dehumanising racialised public spectacle. Slavery and colonialism was and still is a show,” she says.

Muauke is not alone in her indignation. Rune Berglund, head of Norway’s Anti-Racism Centre says: “The only people who will like this are those with racist views. This is something children with African ancestry will hear about and will find degrading. I find it difficult to see how this project could be done in a dignified manner.”

Africans are still dealing with attitudes that suggest an inability to solve their problems. Political crises in Africa, for example, are treated by western media, civil society and governments as evidence of a primitive nature and the need for western intervention (read: civilisation).

The racial superiority complex of the European mind is not a thing of the past. It is a present thing. The Norwegian human zoo is thus not necessarily a mere re-enactment of the past. It is real at many levels.

Fadlabi’s and Cuzner’s goals may be noble but will their project lead to the type of conversations they claim they want it to be part of? Or is it contributing towards the maintenance and resurgence of racist ideologies in the world? Theirs is not the first “artistic product” in the last three years to present Africans on the same footing as animals. Just a few weeks ago, a Belgian newspaper printed a ‘satirical’ article and photos that compared the US president, Barrack Obama, to an ape. The editors claimed that it was mere satire.

In 2012, a Swedish artist made a cake installation of a black woman being cut into, allegedly to provoke discussions around female genital mutilation. A high-ranking politician indeed cut into the black cake, with a human black-painted screaming face. There was laughter and cheers. The discussion on female genital mutilation did not happen. If it did, it was too low-key. The discussion turned onto the representation of black in a world claiming to be liberal.

Art is not innocent. As W E B Du Bois wrote, all art is propaganda. In the cake and human zoo re-enactment incidents, the artists do not deny that their art is not pure. They all lay claim to "noble" causes. They want to create and participate in discussions; discussions of race, oppression, colonialism and the ills of yesterday and today as systematic gender and/or racial oppression. Should artists think more about the impact of their work, especially as regards the possible interpretations of the same work? Should governments funding such projects think deeper about all the possible interpretations?

We are not in a post-racial world. Fadlabi and Cuzner can’t exonerate themselves because they mean well. Indeed, if they are serious about creating discussions of racism they ought to think deeper about the likelihood that their project may entrench the same prejudices they claim to fight.

A longer version of this article first appeared on This is Africa

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion