Most of us don't give much thought to the idea of escaping our problems on Earth by going into space. But those who want to colonize Mars often see it as an urgent need for humanity, to have a potential "second home" as they see it. It's also a common theme of science fiction, for instance in "If I forget thee, Oh Earth" by Arthur C. Clarke. In this case his young protagonist is on the Moon, looking towards the Earth.

It was beautiful, and it called to his heart across the abyss of space. There in that shining crescent were all the wonders that he had never known—the hues of sunset skies, the moaning of the sea on pebbled shores, the patter of falling rain, the unhurried benison of snow. These and a thousand others should have been his rightful heritage, but he knew them only from the books and ancient records, and the thought filled him with the anguish of exile.

Why could they not return? It seemed so peaceful beneath those lines of marching cloud. Then Marvin, his eyes no longer blinded by the glare, saw that the portion of the disk that should have been in darkness was gleaming faintly with an evil phosphorescence: and he remembered. He was looking upon the funeral pyre of a world—upon the radioactive aftermath of Armageddon. Across a quarter of a million miles of space, the glow of dying atoms was still visible, a perennial reminder of the ruinous past. It would be centuries yet before that deadly glow died from the rocks and life could return again to fill that silent, empty world.

Image to the right is the front cover of the first edition of "Expedition to Earth" which has this as one of its stories.

Asimov has a similar idea in his stories - the surface of Earth gradually becomes more and more radioactive in an irreversible process over thousands of years, and eventually humanity has to leave. You can find many stories on a similar vein.

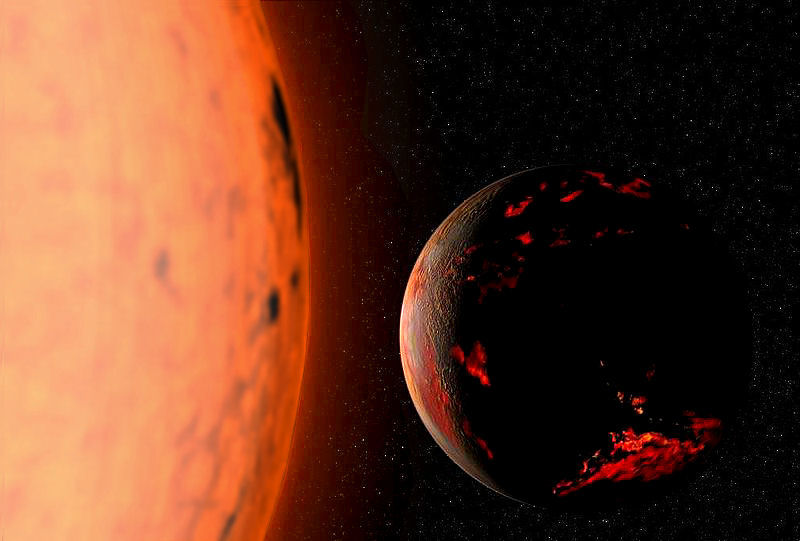

Now, there's no doubt that Earth will become uninhabitable eventually, short of some vast megatechnology (e.g. able to move planets around in the solar system). Roughly a billion years from now the sun will get hotter, as it slowly transitions to its red giant phase - and the seas will boil. Over a long period of time, it will lose all its atmosphere and water and become a dry rocky planet and then will get so hot, the surface rocks will melt. It may get swallowed up by the expanding sun, or it may survive, but for sure the oceans and atmosphere won't survive. See Future of the Earth (wikipedia).

Artist's impression by Fsgregs of a far future Earth after the sun goes red giant. It has lost its oceans and atmosphere long ago. Earth might possibly escape total destruction from the sun however.

If there are any intelligent creatures like us on Earth with space faring capabilities in those times, they will surely leave Earth in their spaceships long before that happens. They might well migrate to Mars which might, in the natural course of events, briefly become habitable as the sun warms up, and be an oasis on the way to Jupiter. Or they might live in free floating settlements made from material from the asteroids and comets, able to survive anywhere in the solar system.

They probably won't resemble us - after all a billion years ago the trilobites probably hadn't evolved yet, indeed it's before the mysterious Ediacaran lifeforms.

The mysterious fractal form of Charnia. Though it looks like a plant or seaweed, it can't be a plant, as it lived at levels of the oceans too deep for photosynthesis. Nobody really knows what it is and how it lived, though it's believed it fed off nutrients in the water. The fossil was found by a school boy Roger Mason, in 1957 - and was actually spotted a year earlier by a 15 year old school girl Tina Negus who told her geography teacher about it - but she simply said it was impossible and didn't bother to follow up her report. You can read her story in her own words here: " An account of the discovery of Charnia"

When the Earth becomes uninhabitable and loses its oceans a billion years from now, our descendants, or descendants of other creatures on Earth, will be at least as far removed from us in time as we are removed from Charnia.

Our descendants would have to leave Earth - but not any time soon.

So for sure we do have to leave Earth - but many have a sense of urgency about this - that we should set up a colony on Mars as soon as possible, even if it turns out that this will make it far harder or impossible to find out in detail what Mars is like in its present biologically reasonably pristine state.

So, could we make Earth uninhabitable? Could we make it so uninhabitable that our descendants need to leave the Earth and migrate into space in the near future, as in the science fiction stories by Arthur C. Clarke, Asimov, and others?

Nuclear test in Bikini Atoll in 1954

Well there is no doubt that a nuclear war would cause many problems on the Earth, especially with the nuclear winter.

The Kuwaiti oil fires in the Gulf war. The thick smoke caused a drop of temperature of the region by several degrees C - but as Carl Sagan wrote, "as events transpired, it was pitch black at noon and temperatures dropped 4-6 C over the Persian Gulf, but not much smoke reached stratospheric altitudes and Asia was spared."

A nuclear winter could cause conditions like that for several years over the entire world.

Then there are various other things, for instance, new diseases that could wipe out humanity.

There are astronomical events also which could cause problems. A giant impact for instance, like the one that brought an end to the dinosaur era.

Artists' impressions of giant impacts on the Earth. Some of these might cause a firestorm over the entire Earth, which burns up just about everything and makes most species extinct over the entire Earth.

That sounds pretty dire. But, the first thing to bear in mind is that these events are rare, only every few tens of millions of years for the largest ones. We can expect many smaller meteorites, before one of these monsters, in ordinary course of events.

Yes, this is going to happen eventually - if we don't find a way to deflect them first. But - "eventually" here means, most likely a few million years from now.

Meanwhile our main priority probably should be tracking the rather smaller city threatening meteorites, which may hit every few centuries. Once we can deal with those, any really large threats should also be easy to spot. We may be able to deflect those also, and at any rate in the not so distant future, with the entire solar system carefully mapped out, right out to the Oort cloud surely if we remain a technological civilization, we will have plenty of warning to decide what to do about them.

Even after a global firestorm, and most species extinct, then the Earth would still have its atmosphere and its oceans. It would be far more habitable than Mars or the Moon. If you were in either of those places, then your best chance of surviving is to get back to Earth, if you can make it here. Because here, you won't need to create your own oxygen, water is abundant, you have protection from cosmic radiation, have normal atmospheric pressure. Any humans left on Earth would have a far better chance of surviving than, say, Mars One or SpaceX colonists on Mars with no support from Earth.

Even after a nuclear war, there would be uninhabitable places on the Earth for sure, but we don't have the technology to make the entire surface of the Earth radioactive.

We can't even make Earth as hazardous to health as the cosmic radiation that bathes the entire surface of Mars. On Mars humans need meters of soil to protect them from cosmic radiation because they don't have the protective atmosphere of the Earth. On Earth even after a nuclear war, you wouldn't need that much protection except at the worst hot spots of radioactivity.

If you can somehow survive the event itself (say underground or beneath the sea) then the Earth would remain a far more benign place to live than anywhere else. And it's far easier to go underground or under the sea for survival than to travel to Mars or the Moon to do that.

If you want to terraform anywhere in the solar system after such an event, then again we are already in the right place. The Earth is the only place that is worth working on, to get a habitable planet again in the shortest possible period of time.

Early science fiction writers had the idea that a nuclear chain reaction could become a runaway reaction in ordinary materials in the Earth's crust and indeed make the whole surface radioactive. Asimov took that idea and with the aid of a bit of sci. fi. technobabble created an almost believable future scenario where it happens as an unstoppable thousands of years long process. But we don't have any way of doing such a thing in reality.

Other cosmic events similarly can't make Earth as uninhabitable as Mars, or at least, the chance is so tiny as to be almost infinitesimal. To take the main examples.

- A nearby supernova. We know all the nearby stars able to go supernova in the next few million years, and none are near enough to cause serious problems to the extent of making the whole Earth uninhabitable.

- A gamma ray burst. This could make half of Earth uninhabitable - but the other half would survive, as it is of such short duration, with the main effect over in seconds, or minutes at the most.

- A black hole. Well this could destroy the Earth. But in practise - though theoretically you could have primordial black holes able to do this - it doesn't seem that there are any, or at least not many, not enough to be an event to worry about. Because the sun still survives. Conceivably there could be an embryo planet that got lost into a black hole, in the early solar system, and we might not notice it. But the sun is a far larger target than any planet. If there were trillions of mini black holes roaming our galaxy, the stars would blink out, and our sun is far more likely to get hit than any planet. There may well be huge black holes, there may even be micro black holes created in the early universe, but they can't be numerous enough to be a big issue for us.

- Impact by an embryo planet or giant comet. These were common in the early solar system. But not likely now. If there were frequent giant comets visiting the inner solar system, we'd see the impact scars on the Mars and the Moon. They do have huge scars, but the really big ones all date back to the first few hundred million years of our solar system. There is one possibility though. Mercury might hit the Earth. But no need to lose any sleep over this. If it happens (itself a low probability event), it will be a billion years from now - gradually perturbed by resonances with Jupiter - and most likely to hit Venus or escape the solar system - but might hit the Earth. If that happens our future descendants may need to worry about it - but not us, not for a few hundred million years at least.

We think we have problems here on the Earth but compared to other places in the solar system, really, we have things easy here.

Mars colonist enthusiasts talk about technological methods which they believe could solve all the problems of Mars. The problem with this as a motivation for colonizing Mars is that the same technology would let you colonize inhospitable areas of the Earth for a far lower cost than Mars.

And on Earth, much of it is not even needed, especially the technology to generate oxygen from ice, or to create buildings able to hold in ten tons per square meter of outwards atmospheric pressure in the near vacuum of Mars, or the technology to protect buildings from cosmic radiation, or the technology for space suits to let you go outside your habitats.

So it doesn't make too much sense to use these expensive technologies to colonize Mars if you are looking for somewhere to live. Far better to do something like the seawater greenhouse or other technologies for reversing desertification on Earth.

WHAT ABOUT ESCAPE TO SPACE FROM EFFECTS OF WAR ON EARTH?

As for escape to space to avoid violent tendencies of humans on Earth - we can only really hope to survive in space if we can learn to be somewhat more peaceful than we are now, not just in space, but on the Earth also.

If you took present day technology and put it back in a time machine to the early twentieth century, I think it's reasonably clear that humans then wouldn't be able to handle it. Without all the understanding and safeguards we developed over the last century, then they might well go extinct in some great war, using biological weapons, jet fighters, nerve gas, and other chemical weapons, atom bombs and so forth.

Similarly if the ordinary person today had the ability to go into space as easily as we can fly in an airplane, including for instance all the countries on the Earth, even the most unstable ones - I'm not sure if we'd survive that level of technology right now. Space settlements would be particularly vulnerable. So - if we do colonize in space, we need to be sure that we do that in a peaceful way, or our attempts will probably not last long, with the fragile colonies and spaceships vulnerable to impacts with tiny pieces of debris travelling at the speeds of interplanetary spaceships. Surely if we are afraid of consequences of our violence on ourselves on Earth - then it's not really the best time to go into space, as similar violence with highly developed space technology would be far worse.

If we attempt to escape into space we will just take all our problems with us, and they would loom far larger in the fragile and difficult conditions of space colonies.

We have made a great beginning here with the Outer Space Treaty with its emphasis on cooperation and peaceful development of space, and with no country able to claim territories in space. I think we need to build on that - but much as one might like to rush into space and develop quickly - perhaps we are better off learning to walk before we run.

WHAT WE WOULD NEED TO DO TO EARTH TO MAKE IT AS INHOSPITABLE AS MARS

To trash Earth enough so that an escape to Mars makes sense we'd have to somehow get rid of all the water - including all the oceans - all the oxygen of course, and nearly all the atmosphere leaving a laboratory vacuum - all the ice also except a fifth of the ice in Antarctica (spread over the surface of Earth would be about equivalent to the ice on Mars) -and get rid of the Earth's magnetic field which protects us from solar storms and also protects water vapour in the upper atmosphere which otherwise would get split and lost.

Then - reduce the amount of sunlight to a half (that by itself is enough to plunge Earth into a snowball phase) - greatly increase meteorite impact rate (because Mars is so close to the asteroid belt) - reduce the gravity to a third (we don't know if this low g is healthy for humans and it means also that you need e.g. three times as much oxygen and nitrogen for the same atmospheric pressure) - and stop continental drift (which on Earth is what returns the CO2 to the atmosphere long term).

You might think that a global firestorm could reduce the amount of oxygen in the Earth's atmosphere, because we rely on plants to create it. But it turns out, we have enough oxygen in the atmosphere already to last us for millennia. Though there are fluctuations every year, due to seasonal effects of plants growing and dying, without this life the oxygen would remain in the atmosphere for thousands of years and just slowly get absorbed in the oceans. Plants and sea algae would grow back within a few years, certainly in centuries, plenty of time to replenish the oxygen again after a firestorm.

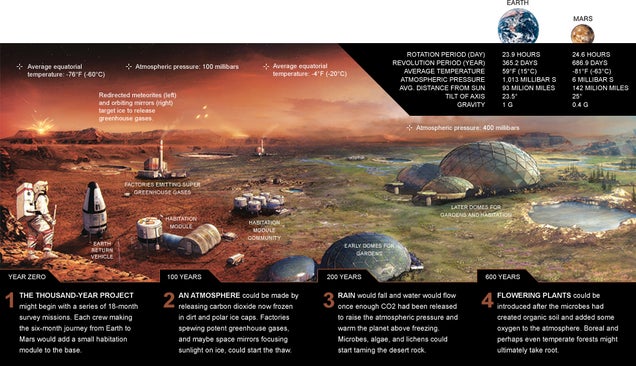

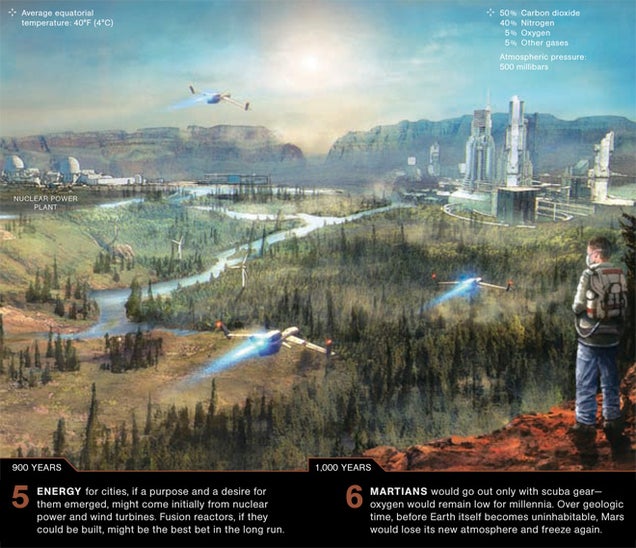

And - those who talk about terraforming Mars may not realize that the most optimistic projections make it a thousand year process. This is how the Mars society imagines it - and they are the most optimistic of all about terraforming (outside of science fiction of course):

When have we ever done a highly technological project that takes a thousand years to reach completion? We have difficulty keeping on track with a technological space project for 20 or 30 years. And those are the projections of the Mars society optimists.

Others think that it would take far longer, at least to have any chance to breath the atmosphere. Chris McKay estimates 100,000 years to a breathable atmosphere - and with many things to go wrong along the way.

The reason for this difference of opinion here is that the oxygen needs to be separated from carbon dioxide, carbonates or water - most likely from carbon dioxide if there is enough of it. To do that using life processes, you need plants to not just grow, but to capture meters thick layers of peat, or other organics over the entire surface of Mars. The carbon you extract from the CO2 has to go somewhere. And you have to counter natural process of decay that recapture the oxygen created as CO2 and return it to the atmosphere, and other processes involving life forms consuming the oxygen as soon as it is created. If you just look at creation of oxygen and ignore its consumption, the situation looks much more optimistic, but realistically, you can't do that without huge megatechnology, e.g. perhaps global greenhouses or some such. At least nowhere on Earth do you get carbon capture fast enough to create an oxygen atmosphere in less than many millennia, and with the reduced light levels on Mars, and the need to create three times as much oxygen for the same atmospheric pressure in the lower gravity of Mars, that becomes Chris McKay's 100,000 years.

We seem to find it impossible on Earth, with all our billions and our vast industry - to adjust the CO2 levels of the Earth's atmosphere back down by 0.01% of the Earth's atmospheric pressure from 400 parts per million back to the pre-industrial 300 parts per million.

If we can't do that, how can anyone suppose a small colony on Mars could keep its atmosphere stable when it starts to go in unexpected directions? Or in the other direction, if we had technology that permitted terraforming Mars then we could stop global warming pretty much overnight.

It just doesn't bear close scrutiny I think. Working through ideas for terraforming Mars I think is of great benefit so long as you keep it to the ideas stage. It's great for clarity of thinking, better understanding of processes of Earth, and understanding how we can re-terraform areas of Earth that become desert like.

But when it comes to actually terraforming other planets, I think we are talking about centuries into the future. That is, unless there is some huge fast increase of understanding and knowledge.

It's probably like interstellar flight. We have many ideas for interstellar flight. Some are actually practical right now. If we desperately needed to do an interstellar flight we could do it with a generational spaceship and using hydrogen bombs to fuel it as in the Orion project design.

Project Orion - this nuclear powered spaceship would weigh thousands of tons, powered by hydrogen bombs. We could build it now (though it would of course violate the nuclear test treaty). A large enough version, using many times the total existing arsenal of nuclear weapons on the Earth could actually travel to nearby stars.

But if we do want to go to other stars, there is no point in setting out right now assuming our technology continues to advance, as spaceships launched a few centuries from now would surely easily overtake these slow interstellar giant ships.

But any spaceship we launch right now would take centuries and most likely thousands of yeas to get there. So long as we continue as a space faring civilization, then future interstellar spaceships would easily overtake the ones launched in the early centuries of a space civilization. As time goes on, through advancing technology, the expected arrival dates of an interestellar spaceship at nearby stars will get earlier and earlier, and for as long as this process continues,it doesn't make much sense to set out on the voyage, except as a desperate last ditch attempt (more about this in the comments to this article).

It's the same with any mega-engineering projects expected to take thousands of years to reach completion. It actually is likely to help to start later - because if you start too soon, then you are likely to do things that will mess it up and make it harder for later engineers.

For instance, Mars has reasonable quantities of dry ice, and water ice at present. This may be useful in the future - but if we were to warm it up now, and things go wrong, it might well combine to make carbonates or in other ways become unavailable to future terraforming attempts. And as already said, any life we introduced can't be removed as far as we know and makes irreversible changes to the planet - which our successors may not welcome.

So, until we know what we are doing, the chances are that we could make other planets worse, especially if you introduce life forms to another planet. That's a big irreversible unknown, what living things would do to future terraforming attempts, if done without understanding the consequences. Introduce species that would fight against the things you wish to achieve and it could set back the process by centuries, or make it impossible.

For that reason, as well as to protect Mars for future scientific study until we know what's there, I think humans with their trillions of microbes in thousands of species should not go anywhere near Mars surface though they could be of great benefit in close to Mars orbit exploring via telepresence, e.g. able to drive a successor to Curiosity tens or even hundreds of kilometers every day and look for life in real time via telepresence.

The rovers are our eyes, and boots, and hands on other worlds at present and I think we need to continue that way - at least for a while yet.

Artist's impression of ExoMars - ESA rover which they plan to send to Mars in 2018 - the first rover since Viking able to search for life directly on Mars. It is able to detect life in the heart of the Atacama desert (which Curiosity couldn't do and only the labelled release experiment on Viking could do - for more on that see Rhythms From Martian Sands - What Did Our Viking Landers Find in 1976? Astonishingly, We Don't Know)

The main focus of ExoMars is on past life, and it is not going to visit the places most habitable for present day life - but does have the capability of spotting present day life as well if it comes across it.

Our current rovers are slow, only able to travel less than 100 meters a day - but future rovers will be able to travel kilometers per day. They will be able to explore a pristine Mars (hopefully anyway if the planetary protection measures to date have worked) because we haven't yet contaminated it with Earth life and haven't yet colonized it.

Later, then we may be able to send humans to Mars orbit to control a wide variety of rovers on the surface in real time, including rovers able to fly, and explore caves and the Valles Marineres and other exciting - and dangerous - places on Mars. As the technology develops we will be able to control mechanical humanoid avatars also - and in that way put "telerobotic" boots on Mars.

Let's keep Mars pristine, at least for a while, so that we can explore it in its original state!

If we find interestingly different life on Mars we may need to keep it free of Earth life indefinitely. If so that should be a cause of celebration as it means Mars is a really interesting place to study and explore, though best done via telepresence at least with present day technology.

We don't need to be depressed at this. But rather, excited. We live in amazing times, with the solar system still relatively pristine, so we can actually look at the planets and see what they were like originally. On Mars, we have the opportunity to study a planet that may well have evolved life independently, quite possibly in a different direction from Earth - or if it evolved similarly to Earth - hasn't had all the traces of the early stages of evolution erased by continental drift. Like Earth, it had oceans and ideal conditions for life in the early solar system. Unlike Earth - much of it surface has remained pretty much unchanged, in a deep freeze, since the very beginnings of the solar system.

If we use these times to just spread the pollution of Earth life to as many places as we can in the solar system, as the colonists wish to do, our future descendants may well look back at our times with regret, and wish they lived now, in times when the solar system was still in such a pristine state, and wonder what knowledge they lost.

I would apply this even to the Moon. Rather than look at the ice at the lunar poles and just think about how best we can use it to spread humans through the solar system - let's instead consider what a wonderful opportunity we have to study these still pristine deposits which may have information about the very early solar system. I think anything like that should be first studied by scientists - and only used for fuel and other resources once we know for sure what it is that we have there. Perhaps some of these deposits might be valuable in other ways - particular craters or particular deposits of especial interest, but there is no way we can judge this now, either way, with our current so limited knowledge of the solar system.

I'm not at all saying we won't or shouldn't set up human colonies in space. Just that, for the time being anyway, these are going to be research outposts, like the settlements in Antarctica - probably with few permanent residents. Simply because it doesn't make practical sense to go anywhere outside of Earth as a permanent place to live, or a second home, no more than it makes sense to live in Antarctica permanently - and Mars, the Moon, and the asteroid belt and all other locations in the solar system are far less hospitable than many relatively uninhabited areas of the Earth such as deserts, and polar regions.

We'll also have industry in space eventually too, surely, do already to some extent with the satellites. We may have humans in space for industrial reasons. But they would be mostly focused on helping the Earth, for instance solar satellites in space to beam power to the Earth, constructed using materials in space. Or building research stations for scientists, and places for tourists to visit. We'll surely have adventurers and explorers exploring the solar system eventually also just as they did in Antarctica. We may have wealthy billionaires who set up permanent homes in space because it's a cool place to live.

But in the near future at least for some time, unless there is some huge game changing technology, I don't see any scope for a second home for humanity in space. At least, not until we have totally sorted out our problems on Earth first. Then we'd go into space and perhaps find second homes there eventually, but not as an escape from Earth, more as part of a process of discovery and adventure and learning new things.

This is Princess Elizabeth research station in Antarctica - Belgium's station, and the first "zero emission" research station in Antarctica; it generates all its own power.

Space colonies, I believe, are likely to start as research stations like this, inhabited mainly by scientists, who are there because they find the solar system utterly fascinating. They will probably have visitors also - tourists, journalists, adventurers and so on, there for shorter periods of time - plus staff who are there to help keep the station running. But for ordinary people, there won't be much of interest to keep you there for months and years on end, and they are certainly not an easy place to set up home in the near future.

What do you think? If you have other ideas about this, or any other thoughts on any of these points do say in the comments and let's have a vigorous discussion! And any questions also, do ask away.

There are several articles about this that I wrote here: Let's Plan For Exploration and Discovery of Space with no End Date - NOT Escape from Earth - Opinion Piece - talks in detail about some of the things we might discovery in space and why our solar system is well worth the trouble and expense of exploring, particularly for life discoveries.

And one that got a lot of attention: Trouble With Terraforming Mars - many details that make Mars so hard to terraform, and some of the many things that could go wrong.

And you can try some of the other articles in my blog at http://science20.com/robertinventor

I originally wrote this as a comment to an interesting article on io9 by Annalee Newitz called "The One Scientific Field Most Likely to Get Humanity Into Space" - it's well worth a read if you haven't seen it, takes another interesting perspective on this whole question.

Comments